Writing about trends makes me cranky, but a paragraph or two seems obligatory.

If one wants already to synthesize the story of New York opera 2006 -- though what was truly important may not become clear for decades -- it's easy to grab on to the Met handover from Joe Volpe to Peter Gelb. The year was rather mixed for both. Volpe's last production showed Otto Schenk at his least defensible, while despite the New York Times-enforced honeymoon for Gelb and his chosen stars (and I think the Times is doing itself and its music writers an unfortunate disservice with this policy), his two new offerings have disappointed. It was the almost-new that did each credit: Lohengrin (mothballed since 1998) in the spring and Butterfly (which, as one may recall, premiered previously at ENO) this fall. Each treated the press with a cynicism (Sunnegårdh/the "everything's new" metastory) that would be appalling if this press didn't seem so happily cooperative.

But of course there were structural decisions that may prove more important: the labor agreement that begat the frequent Met transmissions over Sirius satellite radio, or City Opera's failure to secure a new home.

Fortunately, opera is not about trends or structure, which collectively explain some things but not the very present magic that happens at every good performance -- whether in good artistic climate or bad, as daily occurrence or happy aberration.

So from 2006 I remember that some very interesting tenors bowed, not least Jonas Kaufmann and Joseph Calleja. That baritone Carlos Alvarez did Verdi credit -- twice, and baritone Thomas Hampson (iffy high notes and all -- and they may even have helped) was wrenchingly human as the only human being depicted in Wagner's pageant Parsifal (that is, Amfortas). And that Natalie Dessay did this.

But two nights in particular stand out. October 12 was Dorothea Röschmann's solo recital, and the finest I've seen in many seasons. (If the Met doesn't become a regular operatic home, I hope that her New York recital visits nevertheless continue.) Before that was May 3, which was an even more remarkable thing.

First, it was an outing of the most notable production of the year. As charged by Karita Mattila, the revival of Robert Wilson's Lohengrin was the revelation for eye, ear, brain and heart that every fancy-director production aspires to be but only Herbert Wernicke's Die Frau ohne Schatten (despite flawed casting) has otherwise realized in recent decades here.

Lohengrin performances before May 3 featured Ben Heppner in the title part. May 3 brought the debut of a barely-known tenor, Klaus Florian Vogt.

How often does a performer debut at a great house, in a great production, opposite the greatest performer of his time and produce not only a complete, screaming-audience success, but one that actually puts the co-star in second place? Who shows a vocal quality that no one present could believe except for the fact that all had just heard it? (In fact, I'm not sure I believe it now. The DVD of his subsequent Lohengrin in Baden-Baden comes out in a month, and will perhaps provide some evidence. It also occurs to me that the Met's house tape could appear on Sirius at some point.)

If for nothing but Klaus Florian Vogt's Met debut, 2006 was a very good year for local opera. If for nothing but their neglect of the event, 2006 was a very bad year for the local operatic press.

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Friday, December 29, 2006

Sunday, December 24, 2006

First Emperor followup

Pardon my going offline for a few days. I've added a few links to my initial review.

Some points I neglected: First, I think the chorus did well in the unsympathetic production, which mostly uses them as a static, monolithic bludgeon. They do get to sing the opera's big tune, which unfortunately -- as others have noted -- isn't that memorable. But it's the proto-fascistic ritual chanting of the beginning that's most striking.

Second, it's true that some very successful operas have covered very little overt action or drama at all, including several of my favorites (Bluebeard's Castle, Pelléas et Mélisande -- both discussed previously here). But these pieces use a refined and highly cohesive text and musical language to magnify the inner happenings that are on show. The First Emperor isn't concerned with interiors period; doggedly public, its characters are unindividuated, seemingly by intention. Yet its language and thematic content is still a scramble, and Tan Dun's polyglot score is far from the masterpiece of drama and cohesion that could make sense of the evening on its own.

Third, I agree with Tommasini's critique of the work's one-dimensional handling of vocal lines.

Fourth, I also agree with Lisa Hirsch that Wagner and Mark Adamo have been successful as their own librettists. (Adamo's adaptation of Little Women into a successful piece of theater is brilliant.) But of course pure foolishness does sometimes get things right...

Some points I neglected: First, I think the chorus did well in the unsympathetic production, which mostly uses them as a static, monolithic bludgeon. They do get to sing the opera's big tune, which unfortunately -- as others have noted -- isn't that memorable. But it's the proto-fascistic ritual chanting of the beginning that's most striking.

Second, it's true that some very successful operas have covered very little overt action or drama at all, including several of my favorites (Bluebeard's Castle, Pelléas et Mélisande -- both discussed previously here). But these pieces use a refined and highly cohesive text and musical language to magnify the inner happenings that are on show. The First Emperor isn't concerned with interiors period; doggedly public, its characters are unindividuated, seemingly by intention. Yet its language and thematic content is still a scramble, and Tan Dun's polyglot score is far from the masterpiece of drama and cohesion that could make sense of the evening on its own.

Third, I agree with Tommasini's critique of the work's one-dimensional handling of vocal lines.

Fourth, I also agree with Lisa Hirsch that Wagner and Mark Adamo have been successful as their own librettists. (Adamo's adaptation of Little Women into a successful piece of theater is brilliant.) But of course pure foolishness does sometimes get things right...

Friday, December 22, 2006

Lord of Heaven! How long is this opera? Longer than a hundred wars.

cast | story

A lawyer who represents himself, it is said, has a fool for a client. The same ought to be said for the composer who writes his own libretto. Tan Dun and Ha Jin's leaden, drama-free text for The First Emperor nullifies what seems like lots of creditable work from the many other people involved in the world premiere piece, not least Tan Dun himself (while wearing the composer hat).

The writing is poor in so many ways that it seems unfair to catalog them. Most apparent is the embarrassingly semi-poetic diction, which proves (and more) the dictum that no one has ever been a very good poet outside his own language. Neither librettist is even a poet in Chinese, which (noticably) makes things worse. Metaphors wander in and out with little rhyme or reason, and characters speak in cornball formulations apparently rejected from Star Wars prequels.

But even discounting this as some amusing quasi-foreign patina, the libretto as such fails entirely. Characters: cardboard, or worse. Drama: none to speak of. Neither librettist is a man of the theater (Ha Jin is a novelist and even, according to his in-program interview, demurred from the assignment at first because he knew nothing about opera), and that too shows. They feel no need to show action as such for the first hour, and if this is the sort of insanity that Wagner could make fascinating, they're... not Wagner.

Nor is there a strong thematic or characteristic thread. The title character, whose loss of all beloved in the course of becoming emperor provides what overall plot the opera contains, could be the backbone but isn't. As written for and well-sung by Placido Domingo, he's not any sort of frightening tyrant while onstage but a toothless sitcom dad. There's one bout of scarcely-credible mustache-twirling book-burning at the beginning, but that element is quickly dropped, as every following scene shows Domingo coaxing and wheedling his recalcitrant daughter and foster brother with talk of the good of the country.

That this emperor was not allowed to be shown as even half-frightening and tyrannical is a huge flaw, and several possible reasons came to mind. First, it could be in order to protect and accomodate Domingo's star persona. Second, it could be to avoid offending the Chinese government, whose excesses are clearly allegorized here (at least until the end -- see below). Third, Tan Dun and Ha Jin could actually have thought that the drama was best served by humanizing the character 90-100%, which simply shows their misunderstanding of the stage. None of these possibilities are particularly happy to contemplate.

The other possible thread is in the composer, also well-sung by Paul Groves. Most of the opera agonizes over his dilemma of serving the emperor and getting what he wants or standing up for principle. It is transparently these Chinese artists' self-reflection on their getting quite cozy (rather too so for director Zhang Yimou, whose Hero was an appalling justification of tyranny) with the current Chinese regime... The composer, it turns out, means well, but is seduced by love of the princess to agree to help.

This could go somewhere, but it doesn't. With everyone dropping dead, the composer is shown to die (because the princess died), but also to have had his personal revenge by putting his enslaved people's song of suffering in as the big imperial anthem. This is pure populist hokum -- we're not going to see labor camp songs from any of these folks -- sidestepping the real and perhaps tragic dilemma in which the real artists are enmeshed. Neatly done, but unsatisfying.

What's left? The music. Often derivative -- echoes of everyone from Wagner to Barber and Copland to Puccini (of course) to actual Chinese musicians -- the score nevertheless contains many interesting textures and sonic colors, particularly in the orchestral interludes. (Actually, my favorite part was the bizarrely obvious Stravinsky ripoff.) As absolute music, it deserves a listen, and a concert suite from the opera might be a success. But every time characters appear, the proceedings grind to a halt. Every line, sentiment, and action is telegraphed; the obviousness of it all makes hearing the music as such almost impossible. Indeed, over the radio the piece may even work. But in the theater, it is a terrible waste of time.

If the Met commissions another work from Tan Dun it should be for the Met Orchestra. Please leave opera commissions to people who actually understand opera -- e.g. Tobias Picker.

A lawyer who represents himself, it is said, has a fool for a client. The same ought to be said for the composer who writes his own libretto. Tan Dun and Ha Jin's leaden, drama-free text for The First Emperor nullifies what seems like lots of creditable work from the many other people involved in the world premiere piece, not least Tan Dun himself (while wearing the composer hat).

The writing is poor in so many ways that it seems unfair to catalog them. Most apparent is the embarrassingly semi-poetic diction, which proves (and more) the dictum that no one has ever been a very good poet outside his own language. Neither librettist is even a poet in Chinese, which (noticably) makes things worse. Metaphors wander in and out with little rhyme or reason, and characters speak in cornball formulations apparently rejected from Star Wars prequels.

But even discounting this as some amusing quasi-foreign patina, the libretto as such fails entirely. Characters: cardboard, or worse. Drama: none to speak of. Neither librettist is a man of the theater (Ha Jin is a novelist and even, according to his in-program interview, demurred from the assignment at first because he knew nothing about opera), and that too shows. They feel no need to show action as such for the first hour, and if this is the sort of insanity that Wagner could make fascinating, they're... not Wagner.

Nor is there a strong thematic or characteristic thread. The title character, whose loss of all beloved in the course of becoming emperor provides what overall plot the opera contains, could be the backbone but isn't. As written for and well-sung by Placido Domingo, he's not any sort of frightening tyrant while onstage but a toothless sitcom dad. There's one bout of scarcely-credible mustache-twirling book-burning at the beginning, but that element is quickly dropped, as every following scene shows Domingo coaxing and wheedling his recalcitrant daughter and foster brother with talk of the good of the country.

That this emperor was not allowed to be shown as even half-frightening and tyrannical is a huge flaw, and several possible reasons came to mind. First, it could be in order to protect and accomodate Domingo's star persona. Second, it could be to avoid offending the Chinese government, whose excesses are clearly allegorized here (at least until the end -- see below). Third, Tan Dun and Ha Jin could actually have thought that the drama was best served by humanizing the character 90-100%, which simply shows their misunderstanding of the stage. None of these possibilities are particularly happy to contemplate.

The other possible thread is in the composer, also well-sung by Paul Groves. Most of the opera agonizes over his dilemma of serving the emperor and getting what he wants or standing up for principle. It is transparently these Chinese artists' self-reflection on their getting quite cozy (rather too so for director Zhang Yimou, whose Hero was an appalling justification of tyranny) with the current Chinese regime... The composer, it turns out, means well, but is seduced by love of the princess to agree to help.

This could go somewhere, but it doesn't. With everyone dropping dead, the composer is shown to die (because the princess died), but also to have had his personal revenge by putting his enslaved people's song of suffering in as the big imperial anthem. This is pure populist hokum -- we're not going to see labor camp songs from any of these folks -- sidestepping the real and perhaps tragic dilemma in which the real artists are enmeshed. Neatly done, but unsatisfying.

What's left? The music. Often derivative -- echoes of everyone from Wagner to Barber and Copland to Puccini (of course) to actual Chinese musicians -- the score nevertheless contains many interesting textures and sonic colors, particularly in the orchestral interludes. (Actually, my favorite part was the bizarrely obvious Stravinsky ripoff.) As absolute music, it deserves a listen, and a concert suite from the opera might be a success. But every time characters appear, the proceedings grind to a halt. Every line, sentiment, and action is telegraphed; the obviousness of it all makes hearing the music as such almost impossible. Indeed, over the radio the piece may even work. But in the theater, it is a terrible waste of time.

If the Met commissions another work from Tan Dun it should be for the Met Orchestra. Please leave opera commissions to people who actually understand opera -- e.g. Tobias Picker.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

Next

By now, I assume most people reading this have been made aware of the Met's experiment in blogging the preparation for tomorrow's world premiere: Tan Dun's The First Emperor. Some interesting tidbits there. I don't have huge hopes for the piece itself, but Domingo's last vanity project here actually turned out to be pretty good.

Meanwhile, if you're desperate for advance word, one Opera-Ler talks out of school about the dress rehearsal. It's a grammar nightmare, but funny:

Meanwhile, if you're desperate for advance word, one Opera-Ler talks out of school about the dress rehearsal. It's a grammar nightmare, but funny:

THE LAST EMPEROR is more than a good try, it is a cohesive work marked by a meticulously prepared libretto and score,staged with intelligence, dramatic flare, and skill. The music is an often fadcinating blend of Chinese and postRomantic Viennesisms. telling the story of Emperor Qin and his daughter, and her suitorsQin was the emperor under whoseaegis the Great Wall Was completed. There are many supernatural elements. The problem with the operas is thar it is easily the most depressing musical drama that I have ever witnessed, lacking, for example, the charm of DON CARLO, the insouciant humor of BORIS, or the feckless merriment of PELLEAS.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Love and the City

[UPDATE 1/2009: As Google searches for "Maija Kovalevska" keep coming to this old page, please first read this new post on Kovalevska's 2008 Mimi.]

cast | synopsis | related post

Someday an overly clever General Manager of the Met may try to scrap the production of La Boheme that Franco Zeffirelli opened twenty-five Decembers ago. Its replacement may be more sleek, more up-to-date or "intimate", and perhaps rather more critically praised -- but will nevertheless be a mistake. For despite any nonsense he's perpetrated since (including his part in the current La Scala silliness), this particular Zeffirelli effort is a sort of perfection, and really (with periodic "refurbishment") ought to outlive us all.

The argument that all the stuff onstage (including, per a recent snooty review, "virtually all the milling citizens of Paris" in Act 2) dwarfs the principals misjudges, I think, the effect. In this Boheme (let's not speak of his Met Traviata), the abundant scenery -- human and otherwise -- is all recognizably of a piece: an old Paris, as grandly indifferent to the characters' woes as a Poussin landscape. The contrast -- made not least by Puccini (a master of background touches) himself -- broadens and strengthens the story's power, not least among the opera-novice date set that make up so much of the audience at these revivals. In love, we are all helpless, and it's no small pleasure to imagine ourselves bare of all but love, loss, and jealousy, in a city as recognizably overpowering as the real New York. For a while, anyway.

* * *

The non-enthusiast audience was yet enthusiastic throughout: more so than I was, in fact, for the rather middling performance we all saw. The best moments belonged to soprano Maija Kovalevska (pictured left, in a non-Met Boheme), in only her third Met performance. She was engaged for this debut at a fairly late date when Cristina Gallardo-Domas, perhaps worn out from Butterfly, cancelled this month's run of Mimis.

The non-enthusiast audience was yet enthusiastic throughout: more so than I was, in fact, for the rather middling performance we all saw. The best moments belonged to soprano Maija Kovalevska (pictured left, in a non-Met Boheme), in only her third Met performance. She was engaged for this debut at a fairly late date when Cristina Gallardo-Domas, perhaps worn out from Butterfly, cancelled this month's run of Mimis.

Kovalevska is from Latvia -- a country known of late for models -- and though she may not photograph as a stunner, on stage she cuts a gorgeous figure, perhaps the most striking of this season's performers'. That isn't the most important thing, but I don't think any reviewer's yet noted it. As impressive was the delicately inner-felt "Donde lieta" she sang in Act 3 -- probably the highlight of the evening -- and her Act 4 death scene.

Mimi's most famous moment, of course, comes in Act 1. So does her lover Rodolfo's. But their two arias and the duet ("O soave fanciulla") that follows may not have shown much, for as sensitively as conductor Steven Crawford shaped phrases and textures, so carelessly did he blast the orchestral volume all evening. Mimi fights the orchestra more at the beginning, and before its assault Kovalevska's focused sound had no trouble being heard, but made no impression at climaxes and an indefinite one overall. Whether she (or Villazon, who had much the same problem) could do better with a more balanced accompaniment is to be seen. I wouldn't mind hearing her again.

Anna Samuil, the Musetta here, also debuted in this run. Russian and apparently a former orchestral violinist, Samuil showed an unmissable "Slavic" edge to her voice absent in her former-Soviet colleage's. She did a pretty good job in her big aria, but I wasn't too taken with it all.

* * *

Rolando Villazón is a much more known quantity. His breath and boundless enthusiasm make him, respectively, interesting and beloved. (Saturday's Rigoletto broadcast -- in which he didn't sing -- showed off the latter: as quiz host, he was entirely likeable and charming, even joking about his "Che gelida manina" transposition.) How much his periodic inability to make an impression -- notably in his Act 1 showpieces -- was the fault of his weak (if easily sustained) top notes and how much was Crawford drowning him out, I'm not sure. That people complained of this even under Domingo's baton (such as it is) has me wondering, but he's still a plus.

Interestingly, as an Opera-L poster observes, Villazon, Giuseppe Filianoti, and the newest tenor sensation Joseph Calleja were all finalists in Domingo's Operalia competition in the same year -- 1999. (But compare their ages!)

cast | synopsis | related post

Someday an overly clever General Manager of the Met may try to scrap the production of La Boheme that Franco Zeffirelli opened twenty-five Decembers ago. Its replacement may be more sleek, more up-to-date or "intimate", and perhaps rather more critically praised -- but will nevertheless be a mistake. For despite any nonsense he's perpetrated since (including his part in the current La Scala silliness), this particular Zeffirelli effort is a sort of perfection, and really (with periodic "refurbishment") ought to outlive us all.

The argument that all the stuff onstage (including, per a recent snooty review, "virtually all the milling citizens of Paris" in Act 2) dwarfs the principals misjudges, I think, the effect. In this Boheme (let's not speak of his Met Traviata), the abundant scenery -- human and otherwise -- is all recognizably of a piece: an old Paris, as grandly indifferent to the characters' woes as a Poussin landscape. The contrast -- made not least by Puccini (a master of background touches) himself -- broadens and strengthens the story's power, not least among the opera-novice date set that make up so much of the audience at these revivals. In love, we are all helpless, and it's no small pleasure to imagine ourselves bare of all but love, loss, and jealousy, in a city as recognizably overpowering as the real New York. For a while, anyway.

The non-enthusiast audience was yet enthusiastic throughout: more so than I was, in fact, for the rather middling performance we all saw. The best moments belonged to soprano Maija Kovalevska (pictured left, in a non-Met Boheme), in only her third Met performance. She was engaged for this debut at a fairly late date when Cristina Gallardo-Domas, perhaps worn out from Butterfly, cancelled this month's run of Mimis.

The non-enthusiast audience was yet enthusiastic throughout: more so than I was, in fact, for the rather middling performance we all saw. The best moments belonged to soprano Maija Kovalevska (pictured left, in a non-Met Boheme), in only her third Met performance. She was engaged for this debut at a fairly late date when Cristina Gallardo-Domas, perhaps worn out from Butterfly, cancelled this month's run of Mimis.Kovalevska is from Latvia -- a country known of late for models -- and though she may not photograph as a stunner, on stage she cuts a gorgeous figure, perhaps the most striking of this season's performers'. That isn't the most important thing, but I don't think any reviewer's yet noted it. As impressive was the delicately inner-felt "Donde lieta" she sang in Act 3 -- probably the highlight of the evening -- and her Act 4 death scene.

Mimi's most famous moment, of course, comes in Act 1. So does her lover Rodolfo's. But their two arias and the duet ("O soave fanciulla") that follows may not have shown much, for as sensitively as conductor Steven Crawford shaped phrases and textures, so carelessly did he blast the orchestral volume all evening. Mimi fights the orchestra more at the beginning, and before its assault Kovalevska's focused sound had no trouble being heard, but made no impression at climaxes and an indefinite one overall. Whether she (or Villazon, who had much the same problem) could do better with a more balanced accompaniment is to be seen. I wouldn't mind hearing her again.

Anna Samuil, the Musetta here, also debuted in this run. Russian and apparently a former orchestral violinist, Samuil showed an unmissable "Slavic" edge to her voice absent in her former-Soviet colleage's. She did a pretty good job in her big aria, but I wasn't too taken with it all.

Rolando Villazón is a much more known quantity. His breath and boundless enthusiasm make him, respectively, interesting and beloved. (Saturday's Rigoletto broadcast -- in which he didn't sing -- showed off the latter: as quiz host, he was entirely likeable and charming, even joking about his "Che gelida manina" transposition.) How much his periodic inability to make an impression -- notably in his Act 1 showpieces -- was the fault of his weak (if easily sustained) top notes and how much was Crawford drowning him out, I'm not sure. That people complained of this even under Domingo's baton (such as it is) has me wondering, but he's still a plus.

Interestingly, as an Opera-L poster observes, Villazon, Giuseppe Filianoti, and the newest tenor sensation Joseph Calleja were all finalists in Domingo's Operalia competition in the same year -- 1999. (But compare their ages!)

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Isn't it romantic?

A friend sends this note about last night's designatedly young and non-gay Met singles event:

Of course, there was an opera performance, too. Boheme, to be exact.

More to the point, I doubt Boheme is a piece that will particularly draw single men. If gender imbalance is a recurring problem in these things, why not adjust for it?

Finally, it seems that the Met actually has adopted or anticipated Maury and Jonathan's joke by making the season's second Jenufa a singles event. What the heck?

Singles night at the Met is three girls to one guy, and when I looked at the mingling area from the balcony of family circle there were a lot of balding guys, not that they have any control over that problem. Just an observation.(An old post on the Met's initial foray into this territory -- featuring the same problem! -- is here.)

Of course, there was an opera performance, too. Boheme, to be exact.

I thought Samuil was very good, and Kovalevska was talented, but she isn't a very charming Mimi. I forgot that Villazon was Rodolfo, and during the first act, thought, who is this guy that just got out of opera school, 1/2 the time he can't project over the orchestra. When his groupies applauded enthusiastically, I thought, WTF? And then I looked at my program and saw who it was.Singers aside, I wonder why La Boheme was the opera picked: it seems to me an opera better appreciated in the light of a past love than a future one. (Compare, say, Elisir, or Meistersinger -- though of course the latter's far too long for this sort of thing.) Of course, opera romance usually ends badly; wherever the art's reputation as a "romantic" pastime may come (I suspect it's to do with the general fact of women liking it more than men), I have a hard time seeing a basis for it in what's usually on stage.

More to the point, I doubt Boheme is a piece that will particularly draw single men. If gender imbalance is a recurring problem in these things, why not adjust for it?

Finally, it seems that the Met actually has adopted or anticipated Maury and Jonathan's joke by making the season's second Jenufa a singles event. What the heck?

Why the fuss?

Browsing around blogland, I was surprised to see that the Alagna story had visibly spread outside the music/opera blog ghetto. To be sure, most posts there were of the short note and link variety, but there seems to be something to the story to catch a blogger's eye, as indeed it's caught the eye of the regular press.

Part of it is, maybe, old stereotyping about opera and its stars, but why do people even care? The interest, I think, isn't unique to opera: a star acting against his public is news almost by definition, as a politican is when doing the same. He makes his own privileged position the issue, leading usually to one of the classic dramatic resolutions: either he becomes the folk hero (that is, pop star) who is actually beloved for getting away with such things, or he's brought down a peg (or two, or a dozen) for his transgression. (Or, sometimes, the whole affair complicates into pure farce...) In any case, the public is satisfied.

What will result here? A bit of everything, I think. Joe Volpe routed Kathleen Battle, whose career petered out fairly quickly after the famous firing. But pure name recognition seems valued more than ever, and in an ever-more crowded field of tenors, Alagna's done a good job of getting his own name press. Is there still such a thing as bad publicity? Perhaps. At any rate, the wild accusations, threats of lawsuit, and claims of conspiracy are keeping the buffo strand no less spotlit than the tragic or popular.

Part of it is, maybe, old stereotyping about opera and its stars, but why do people even care? The interest, I think, isn't unique to opera: a star acting against his public is news almost by definition, as a politican is when doing the same. He makes his own privileged position the issue, leading usually to one of the classic dramatic resolutions: either he becomes the folk hero (that is, pop star) who is actually beloved for getting away with such things, or he's brought down a peg (or two, or a dozen) for his transgression. (Or, sometimes, the whole affair complicates into pure farce...) In any case, the public is satisfied.

What will result here? A bit of everything, I think. Joe Volpe routed Kathleen Battle, whose career petered out fairly quickly after the famous firing. But pure name recognition seems valued more than ever, and in an ever-more crowded field of tenors, Alagna's done a good job of getting his own name press. Is there still such a thing as bad publicity? Perhaps. At any rate, the wild accusations, threats of lawsuit, and claims of conspiracy are keeping the buffo strand no less spotlit than the tragic or popular.

Wednesday, December 13, 2006

Rigoletto

cast | synopsis | previous year's post: 2005

Tenor Joseph Calleja, soprano Ekaterina Siurina, and conductor Friedrich Haider made their Met debuts earlier in the season in Verdi's evergreen Rigoletto. Baritone Carlos Alvarez made his house role debut in the title part last Friday. So I caught these principals working for the second time together last night, in a big success.

Calleja is, I think, most interesting -- and possibly controversial. I have no idea how it comes across on radio, but his voice in person is a marvel. Effortlessly large but not weighty, it has an unmistakable throwback (to the era of shellac!) character featuring a prominent vibrato I could listen to all day. But it's not only the sound that recalls the golden age, but his control: he doesn't strain, and his phrases are built on a rock-solid sense of time that could be the envy of anyone. Between these and his masculine ease on stage I'm hugely excited for the future; never mind that the top notes, tonight, seemed not to fit into his production. Sound with this much character comes along so rarely.

Still, I see that he already has his share of detractors. I wonder if he, like the shamefully under-engaged Sondra Radvanovsky, has too distinctive a sound to be fairly valued by publicity-makers and the Met. Maybe being a tenor will help (though being a bona fide dramatic coloratura hasn't much helped Radvanovsky).

Siurina has potential but is at the moment less interesting. She has a fresh, pleasant sound through most of her range and decent vocal size; only the very top shows that Slavic edge. She certainly looks good: not unlike a several-dress-sizes-larger Netrebko. And she's willing to move, spin around in the middle of "Caro nome" (which was pretty well sung, despite a high note in the cadenza that literally didn't sound at all), etc. Siurina's Gilda was a convincingly eager young woman, but she didn't much sound the undercurrent of deep feeling that makes the character so memorable.

Alvarez had the biggest success of the night, and deservedly so. He's the first larger-than-life Rigoletto here in a long time, both vocally and in manner. He paced himself vocally through the first duet with Gilda, though with Haider's dragging tempo on the latter I'm not sure he could have shown much anyway. But after that -- from "Cortigiani" on -- he was really good. His Rigoletto was miserable even at home, as perhaps he should be: wracked with worries and hatreds, wound so tight that even courtiers fear him.

In the smaller parts, ageless Robert Lloyd (who, bizarrely, seems to be engaged as the Second Guard for the Met's kiddie Flute) and Nancy Fabiola Herrera did well as assassin and accomplice-sister, while James Courtney wasn't as authoritative a Monterone as he was last season.

Haider led a semi-"authenticized" version, with some traditional cuts restored and interpolated high notes axed. In his actual conducting, he did well leading a light, mostly-bouyant account of the score with clear textures from the orchestra, but seemed uninterested in the most important part -- maintaining the vitality, drama, and proportion of the Act I scene 2 duets between Gilda, her father, and her suitor. These private interactions (and Gilda's aria, "Caro nome", in between) -- by turns agitated, pleading, and rapturous -- define the characters and the intersection of their passions that drives the story; they are the heart of the opera. Sagging here is, unfortunately, also traditional, but the underrated Ascher Fisch did a tremendous job with the scene (and the rest of the piece) last year.

Had Fisch been in the pit, this could have been the event of the season; as it happened, it was "just" a fine evening of opera.

Tenor Joseph Calleja, soprano Ekaterina Siurina, and conductor Friedrich Haider made their Met debuts earlier in the season in Verdi's evergreen Rigoletto. Baritone Carlos Alvarez made his house role debut in the title part last Friday. So I caught these principals working for the second time together last night, in a big success.

Calleja is, I think, most interesting -- and possibly controversial. I have no idea how it comes across on radio, but his voice in person is a marvel. Effortlessly large but not weighty, it has an unmistakable throwback (to the era of shellac!) character featuring a prominent vibrato I could listen to all day. But it's not only the sound that recalls the golden age, but his control: he doesn't strain, and his phrases are built on a rock-solid sense of time that could be the envy of anyone. Between these and his masculine ease on stage I'm hugely excited for the future; never mind that the top notes, tonight, seemed not to fit into his production. Sound with this much character comes along so rarely.

Still, I see that he already has his share of detractors. I wonder if he, like the shamefully under-engaged Sondra Radvanovsky, has too distinctive a sound to be fairly valued by publicity-makers and the Met. Maybe being a tenor will help (though being a bona fide dramatic coloratura hasn't much helped Radvanovsky).

Siurina has potential but is at the moment less interesting. She has a fresh, pleasant sound through most of her range and decent vocal size; only the very top shows that Slavic edge. She certainly looks good: not unlike a several-dress-sizes-larger Netrebko. And she's willing to move, spin around in the middle of "Caro nome" (which was pretty well sung, despite a high note in the cadenza that literally didn't sound at all), etc. Siurina's Gilda was a convincingly eager young woman, but she didn't much sound the undercurrent of deep feeling that makes the character so memorable.

Alvarez had the biggest success of the night, and deservedly so. He's the first larger-than-life Rigoletto here in a long time, both vocally and in manner. He paced himself vocally through the first duet with Gilda, though with Haider's dragging tempo on the latter I'm not sure he could have shown much anyway. But after that -- from "Cortigiani" on -- he was really good. His Rigoletto was miserable even at home, as perhaps he should be: wracked with worries and hatreds, wound so tight that even courtiers fear him.

In the smaller parts, ageless Robert Lloyd (who, bizarrely, seems to be engaged as the Second Guard for the Met's kiddie Flute) and Nancy Fabiola Herrera did well as assassin and accomplice-sister, while James Courtney wasn't as authoritative a Monterone as he was last season.

Haider led a semi-"authenticized" version, with some traditional cuts restored and interpolated high notes axed. In his actual conducting, he did well leading a light, mostly-bouyant account of the score with clear textures from the orchestra, but seemed uninterested in the most important part -- maintaining the vitality, drama, and proportion of the Act I scene 2 duets between Gilda, her father, and her suitor. These private interactions (and Gilda's aria, "Caro nome", in between) -- by turns agitated, pleading, and rapturous -- define the characters and the intersection of their passions that drives the story; they are the heart of the opera. Sagging here is, unfortunately, also traditional, but the underrated Ascher Fisch did a tremendous job with the scene (and the rest of the piece) last year.

Had Fisch been in the pit, this could have been the event of the season; as it happened, it was "just" a fine evening of opera.

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

Two waves

Time has cycled around to this blog's second birthday. For those who haven't followed its entire life (or who -- as I have -- have just forgotten things), I offer a sample of posts here to date:

On Don Carlo[s](More reviews can be found in the seasonal compilations to the right.)

Review -- Julie Taymor's Magic Flute (revived later this month in English)

On song recitals (warning: broken links)

On La Clemenza di Tito

On Rostand and Alfano's Cyrano de Bergerac

On Marcelo Alvarez and Manon

On Maeterlinck and Dukas' Ariane et Barbe-Bleue

On the 2005 opera funding crisis in Italy

On the world premiere of Tobias Picker's An American Tragedy (and more)

On attention, onstage and off

On applause

Review -- Robert Wilson's Lohengrin

Review -- Röschmann/Bostridge duo recital

On the passing of Elisabeth Schwarzkopf

On the Joe Volpe era

Review -- recitals by Kožená and Röschmann

To be honest, I'm not very satisfied. But that's what keeps me at it, I suppose.

[UPDATE 2008: I am appending subsequent "selected posts" lists to this post.]

On the world premiere of Tan Dun's The First Emperor

On Ramon Vargas in Onegin

On Meistersinger and Simon Boccanegra

On Strauss and Hofmannsthal's Die Ägyptische Helena

On Ruth Ann Swenson

On the "theatricality" of Met movie broadcasts

Review -- Matthias Goerne in recital

On vocal and theatrical values in historic context

On Peter Davis' exit

On a pop fan's discovery of opera

On Wagner's Ring

On Pavarotti's death

Review -- Mary Zimmerman's season-opening Lucia

On Samuel Barber's Vanessa

On Puccini's Manon Lescaut

On Johan Botha as Otello

On Peter Grimes as sea god (see second part of post)

On Ernani and Verdi's later tragedies

Review -- Ruth Ann Swenson in La Traviata

On Tristan & Isolde and Heppner & Voigt

On Ramon Vargas' unscheduled appearance in Ballo

On Jonathan Miller's jealous realism

Review -- Anja Harteros in La Traviata

On Gerard Mortier's abandonment of City Opera

On Maija Kovalevska and Puccini's La Boheme

On Puccini's La Rondine and Angela Gheorghiu

On Swiss soprano Lisa Della Casa's 90th birthday

On Verdi's Il Trovatore

On Dvorak's Rusalka

On Mary Zimmerman's production of Sonnambula

Review -- Metropolitan Opera 125th Anniversary Gala

On Diana Damrau's Gilda in Rigoletto

Review -- Rene Pape's recital debut

On the season's last Walküre

On Britten's Rape of Lucretia

On Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots

On the premiere of Luc Bondy's Tosca production

On Strauss and Hofmannsthal's Der Rosenkavalier

Review -- Carmen

On Riccardo Muti and Verdi's Attila

On Ambroise Thomas' Hamlet

Review -- Rossini's Armida

On the April revival of Tosca

On Ligeti's Le Grand Macabre

OT: a week of Sleeping Beauty at ABT

Review -- Robert LePage's Opening Night Rheingold

On OONY's Mascagni/Massenet double-bill

On Verdi's Il Trovatore in revival

On Strauss' Intermezzo at City Opera

On debuting tenor Yonghoon Lee as Don Carlo

On the baloney brutality of Willy Decker's Traviata

On Meyerbeer's L'Africane

On Tchaikovsky's Queen of Spades and Russian Francophilia

On Schubert's Edenic Die schöne Müllerin

On Strauss' Capriccio

On Lully's Atys

Review: Siegfried

On Angela Gheorghiu and Cilea's Adriana Lecouvreur

On Manon, Manon Lescaut, and Laurent Pelly's production of the former

On Janacek's tragic version of The Makropoulos Case

On the Peter Gelb era at the Metropolitan Opera

On Verdi's Requiem in performance

Amber Wagner in Ballo

On the struggle against time in Les Troyens

Review: Maria Stuarda and a DiDonato recital

On the Francois Girard/Met Parsifal's Parsifal, cast, conductor, physical production, and meaning

On the entrance of story into the Ring in The Valkyrie

Sondra Radvanovsky in Norma

Monday, December 11, 2006

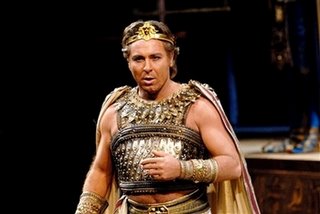

Maybe it was the gladiator costume?

The AP has an article, with picture, on Alagna's walk-off from La Scala's new Zeffirelli Aida.

The AP has an article, with picture, on Alagna's walk-off from La Scala's new Zeffirelli Aida.More interestingly, Opera-L has a first-person account by one of the loggionisti (upstairs ultras whose booing triggered this incident).

I'm pretty much pro-booing but this idea of "traditional" booing as appropriate hazing isn't much to my liking.

Portion control

Austrian mezzo Angelika Kirchschlager was scheduled to give a duo recital yesterday with Barbara Bonney, but Bonney's temporary (?) departure from performing left Kirchschlager carrying the day solo. Perhaps this explains how she ended up getting in her own way.

Kirchschlager offered twelve Schumann songs before the break ("Freisinn", "Erstes Grün", "Hoch, hoch sind die Berge", "Die Soldatenbraut", "Liebeslied", "Das verlassne Mägdelein", "Stille Tränen", "Die Löwenbraut", "Lust der Sturmnacht", "Morgens steh' ich auf und frage", "Der Einsiedler", and "Abendlied") and eleven by Schubert after ("Auf dem See", "Das Echo", "Des Mädchens Klage", "Nähe des Geliebten", "Bei dir allein", "Wiegenlied", "Der Pilgrim", "Sehnsucht", "Lied des Florio", "An den Mond", and "An die Musik").

As you can see, each half was about as heterogeneous a lineup as one could get with a single composer. The songs came one after the other, without apparent theme or progression. It was, in other words, like listening to a CD -- a very enjoyable one, as she was in delicious voice.

But in listening to even Schumann or Schubert from a smorgasbord CD, one doesn't give unmoving attention for a disc-length span. Without the continuity or drama of a cycle or thematic set, one's engagement drifts in and out; adapting one's ear to one different thing after another is fatiguing. Recitalists these days tend to take this into account, breaking up into shorter sets what could be a too-long cavalcade of songs.

But with no set breaks (and no "applause line" finishes in the early songs), the mostly well-behaved Alice Tully audience had no opportunities to reset its focus and attention. This, unfortunately, prompted a pretty consistent background of coughs and fidgets (and one quickly-stilled cell phone) that threw Kirchschlager off. What made it worse was the lack of applause points gave no occasion for the audience to engage positively with Kirchschlager before intermission either. CD-style listening passivity was, unfortunately, maintained, and her performance reflected that.

Applause at the half was enthusiastic, which I think surprised her. But the Schubert half brought back the original dynamic, with Kirchschlager's irritation growing more obvious (and her singing more remote) until she actually stopped to chide the audience about the importance of silence. This didn't, mind you, have much effect, and she looked several times as if she might stop again. Nevertheless, she sang her best at the end here.

After a storm of applause, she gave two encores -- Schumann's "Widmung" and a Poulenc song -- with vivid expressive freedom but tiring breath. Had she defused audience-performer tension nearer the start, it might have been a great afternoon.

As it was, the most successful songs were two of the narratives -- Die Löwenbraut and Der Pilgrim -- in which she gave lively voice to contrasting moods and events.

Recitalists, please: unless it's "Winterreise", leave some room for applause.

UPDATE (11AM): I forgot the oddest development -- by the last few songs, Kirchschlager herself took to coughing between songs. Whether this was actual distress or sarcastic commentary, I honestly couldn't tell.

Kirchschlager offered twelve Schumann songs before the break ("Freisinn", "Erstes Grün", "Hoch, hoch sind die Berge", "Die Soldatenbraut", "Liebeslied", "Das verlassne Mägdelein", "Stille Tränen", "Die Löwenbraut", "Lust der Sturmnacht", "Morgens steh' ich auf und frage", "Der Einsiedler", and "Abendlied") and eleven by Schubert after ("Auf dem See", "Das Echo", "Des Mädchens Klage", "Nähe des Geliebten", "Bei dir allein", "Wiegenlied", "Der Pilgrim", "Sehnsucht", "Lied des Florio", "An den Mond", and "An die Musik").

As you can see, each half was about as heterogeneous a lineup as one could get with a single composer. The songs came one after the other, without apparent theme or progression. It was, in other words, like listening to a CD -- a very enjoyable one, as she was in delicious voice.

But in listening to even Schumann or Schubert from a smorgasbord CD, one doesn't give unmoving attention for a disc-length span. Without the continuity or drama of a cycle or thematic set, one's engagement drifts in and out; adapting one's ear to one different thing after another is fatiguing. Recitalists these days tend to take this into account, breaking up into shorter sets what could be a too-long cavalcade of songs.

But with no set breaks (and no "applause line" finishes in the early songs), the mostly well-behaved Alice Tully audience had no opportunities to reset its focus and attention. This, unfortunately, prompted a pretty consistent background of coughs and fidgets (and one quickly-stilled cell phone) that threw Kirchschlager off. What made it worse was the lack of applause points gave no occasion for the audience to engage positively with Kirchschlager before intermission either. CD-style listening passivity was, unfortunately, maintained, and her performance reflected that.

Applause at the half was enthusiastic, which I think surprised her. But the Schubert half brought back the original dynamic, with Kirchschlager's irritation growing more obvious (and her singing more remote) until she actually stopped to chide the audience about the importance of silence. This didn't, mind you, have much effect, and she looked several times as if she might stop again. Nevertheless, she sang her best at the end here.

After a storm of applause, she gave two encores -- Schumann's "Widmung" and a Poulenc song -- with vivid expressive freedom but tiring breath. Had she defused audience-performer tension nearer the start, it might have been a great afternoon.

As it was, the most successful songs were two of the narratives -- Die Löwenbraut and Der Pilgrim -- in which she gave lively voice to contrasting moods and events.

Recitalists, please: unless it's "Winterreise", leave some room for applause.

UPDATE (11AM): I forgot the oddest development -- by the last few songs, Kirchschlager herself took to coughing between songs. Whether this was actual distress or sarcastic commentary, I honestly couldn't tell.

The occasion

cast | synopsis | previous posts: 1 2 3

From inside the house, I haven't yet noticed a difference between Met evenings with Sirius transmissions and those without. Whether it's too new, too common, or too narrow, the fact of an evening's going over satellite radio doesn't, apparently, affect the atmosphere. But the traditional Saturday afternoon radio broadcasts, whether now redundant or not, still seem to count for something: Saturday's season-last Idomeneo showed a remarkable unanimity of focus and inspiration. Despite at least one bashful cell-owner, it was the best opera performance I've seen all season.

Interestingly, even nit-pick issues I had that wouldn't have been noticed on radio -- e.g. Kozena's gestural overshoot and Rensberg's head-bobbing -- were largely corrected. It showed an attention to detail that didn't exclude, for the first time this run, concentration through each act so that each came as one long breath. What a change from Thursday's disappointment...

From inside the house, I haven't yet noticed a difference between Met evenings with Sirius transmissions and those without. Whether it's too new, too common, or too narrow, the fact of an evening's going over satellite radio doesn't, apparently, affect the atmosphere. But the traditional Saturday afternoon radio broadcasts, whether now redundant or not, still seem to count for something: Saturday's season-last Idomeneo showed a remarkable unanimity of focus and inspiration. Despite at least one bashful cell-owner, it was the best opera performance I've seen all season.

Interestingly, even nit-pick issues I had that wouldn't have been noticed on radio -- e.g. Kozena's gestural overshoot and Rensberg's head-bobbing -- were largely corrected. It showed an attention to detail that didn't exclude, for the first time this run, concentration through each act so that each came as one long breath. What a change from Thursday's disappointment...

Saturday, December 09, 2006

Ortrud's sister

Halfway through act I of Mozart's Idomeneo -- which, at 1PM ET today, begins this season of free broadcasts from the Met -- visiting lovestruck princess Elettra addresses the Furies:

And still... Immediately after Elettra's aria we hear a truly infernal storm in the orchestra and chorus, a storm in which one hears much of Don Giovanni's later visitors. Neptune has set the plot proper moving by wrecking Idomeneo's ship and forcing him to promise a sacrifice (of, it turns out, his son and Elettra's desire Idamante) for his own survival. In a sense this is just recapping for the audience what has more or less already been announced by Arbace in the previous scene -- Idomeneo's wreck at sea -- but its timing juxtaposes the knot of the drama with its only human antagonist, and Neptune with her underworld Furies.

The god does take a destructive, demanding role for most of the opera, hounding Idomeneo and his people into fulfilling the impossible bargain. (It is this, I suppose, from which Neuenfels derived the anti-religious premise of his stupid if even more stupidly controversial Berlin staging.) And yet, he is also the one to let them off the hook at the end, accepting love and abdication in the place of (further) death. This dual understanding of the divine seems pretty Greek, but leaves one wondering what exactly the story was supposed to be about.

Perhaps it's a tale about our behavior under misfortune. Ilia and Idamante hold close to love, and they are exalted. Idomeneo pushes others away, and himself into isolation -- and he is stripped of office. And Elettra indulges her envy and resentment, and is struck down by them.

Not exactly innovative, but the real story is in the music, in the how they all bear it.

Tutte nel cor vi sento,It is a terrible and uncanny piece, anticipating the bloody mood of Ortrud's curse. Yet unlike that villain of Lohengrin, Elettra seems to be addressing internal spirits, and she does nothing overt to pursue her vengeance.

Furie del crudo averno,

Lunge a sì gran tormento

Amor, mercè, pietà.

Chi mi rubò quel core,

Quel che tradito ha il mio,

Provi dal mio furore,

Vendetta e crudeltà.

And still... Immediately after Elettra's aria we hear a truly infernal storm in the orchestra and chorus, a storm in which one hears much of Don Giovanni's later visitors. Neptune has set the plot proper moving by wrecking Idomeneo's ship and forcing him to promise a sacrifice (of, it turns out, his son and Elettra's desire Idamante) for his own survival. In a sense this is just recapping for the audience what has more or less already been announced by Arbace in the previous scene -- Idomeneo's wreck at sea -- but its timing juxtaposes the knot of the drama with its only human antagonist, and Neptune with her underworld Furies.

The god does take a destructive, demanding role for most of the opera, hounding Idomeneo and his people into fulfilling the impossible bargain. (It is this, I suppose, from which Neuenfels derived the anti-religious premise of his stupid if even more stupidly controversial Berlin staging.) And yet, he is also the one to let them off the hook at the end, accepting love and abdication in the place of (further) death. This dual understanding of the divine seems pretty Greek, but leaves one wondering what exactly the story was supposed to be about.

Perhaps it's a tale about our behavior under misfortune. Ilia and Idamante hold close to love, and they are exalted. Idomeneo pushes others away, and himself into isolation -- and he is stripped of office. And Elettra indulges her envy and resentment, and is struck down by them.

Not exactly innovative, but the real story is in the music, in the how they all bear it.

Friday, December 08, 2006

Don Carlo quickly revisited

On the one hand, it is a performance where even the tenor and baritone break out trills as needed.

On the other hand, Johan Botha's acute legato deficiency really is a deal-breaker. And so, discouragingly, is Levine's below-par conducting: last night was all generalized, impenetrable urgency, in which even the phrases of usual solo notables Steve (now "Stephen") Williamson (clarinet) and Rafael Figueroa (cello) sounded undistinguished.

On the other hand, Johan Botha's acute legato deficiency really is a deal-breaker. And so, discouragingly, is Levine's below-par conducting: last night was all generalized, impenetrable urgency, in which even the phrases of usual solo notables Steve (now "Stephen") Williamson (clarinet) and Rafael Figueroa (cello) sounded undistinguished.

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

Still naked

No, I had nothing to do with this booing of Domingo for his podium work in Boheme, but I do agree with the sentiment.

UPDATE (12/8): The press takes notice. And see also Maury's personal account of the evening.

UPDATE (12/8): The press takes notice. And see also Maury's personal account of the evening.

Tuesday, December 05, 2006

Low-voice highlights of "Don Carlo"

cast | synopsis | previous years' posts: 2005 (1 2)

The names involved in this month's revived Don Carlo do not, unfortunately, tell its tale. What looked on paper to be the surefire hit of the season is the most disparate amalgam of success and... non-success at the Met in years.

The success is, more or less, Act IV. On Monday Rene Pape kicked off the act with an astounding version of Philip II's aria: I actually found his much-praised performance of this piece (which I may YouTube) at the Volpe Gala a bit too much about muscle and generalized feeling, but this was as natural and detailed as one could want. Then Sam Ramey, wobbly old voice and all, was even more terrifying and authoritative in the Grand Inquisitor part. Together: an impressive jolt.

Who else? Olga Borodina (Eboli), last seen stealing the show in La Gioconda. Here she's among an even starrier cast, and though her high notes are a bit cautious (no serious problem though -- perhaps shedding the eyepatch that she'd worn for last week's prima fixed something?), the dominant impression was of her sound: a rich, pearly thing that somehow makes other instruments sound ordinary, even amateurish. Yes, even in this company.

Finally, the act's second scene showcased Dmitri Hvorostovsky (Rodrigo/Posa), whose refined, flamboyant, and long-breathed singing makes quibbles about stamina and power seem petty.

Those are the plusses -- four stars, doing their bit and feeding off each other.

On the other side, surprisingly, is James Levine. He came terrifically to life with Pape and Ramey in Act IV, leaving one to wonder, what was going on before? Aimless and a bit indulgent, the first three acts passed with little of note: even the auto-da-fe barely registered. Odd. (He was on a terrific run of form before his March injury, but maybe it's not coincidence that he's not led a great Levine performance since?)

But the real lesson, I think, is that though Don Carlo(s) can rightly be described as an ensemble opera, it depends heavily on its lead pair to make dramatic sense. The thing is, neither Johan Botha (Carlo himself) nor Patricia Racette (Elisabeth) are actually bad in this. They're just ill suited to their parts and each other.

Botha, as one might remember from Aida, can sing loudly all day long. But he makes nonsense of his character, and of the plot. There are lots of things one might call Carlo: feckless, hapless, immature, in way over his head. But he must be ardent, or the story makes no sense -- for what else could Elisabeth, Rodrigo, and Eboli see in him, and induce them to invest so heavily in his person? It's this side of the character that the restored Fontainebleau scene (Act I, that is) should let shine, but not here. Botha's physical presence is pretty lumbering, yes, but a certain amount of that is forgiveable in opera. But his sense of phrase and rhythm is similarly earthbound, and with facial expressions that range from a smile to a stronger smile, he's got nothing but power with which to win over the listener. No ardor -- of the Italian variety anyway.

With such a partner, maybe I shouldn't blame Racette. But she too seems miscast. She is audible from the bottom to the top of her range, but the top relies heavily on the penetrating timbre of her strong vibrato. It's an ache-filled, almost desperate sound (you can almost feel her melting into the note), perfect for certain things (including her consolation of her attendant, "Non pianger") but impossible in the joy-of-singing romp of the Fontainebleau love duet and, thereafter, jarringly un-regal. Perhaps in compensation, she seems endlessly focussed on holding her body still: whatever the reason, this mostly just makes the performance more remote.

The low-voiced characters of Don Carlo are, unfortunately, satellites in the Carlo/Elisabeth-centered plot. They can't make the whole evening work.

* * *

The last revival here had somewhat smaller names -- Radvanovsky, Margison/Villa, d'Intino/Urmana, Croft, Furlanetto, and Burchuladze -- but vivid performances all around, and left one with a sense of the opera's greatness. That this revival leads some to doubt Verdi is depressing.

The names involved in this month's revived Don Carlo do not, unfortunately, tell its tale. What looked on paper to be the surefire hit of the season is the most disparate amalgam of success and... non-success at the Met in years.

The success is, more or less, Act IV. On Monday Rene Pape kicked off the act with an astounding version of Philip II's aria: I actually found his much-praised performance of this piece (which I may YouTube) at the Volpe Gala a bit too much about muscle and generalized feeling, but this was as natural and detailed as one could want. Then Sam Ramey, wobbly old voice and all, was even more terrifying and authoritative in the Grand Inquisitor part. Together: an impressive jolt.

Who else? Olga Borodina (Eboli), last seen stealing the show in La Gioconda. Here she's among an even starrier cast, and though her high notes are a bit cautious (no serious problem though -- perhaps shedding the eyepatch that she'd worn for last week's prima fixed something?), the dominant impression was of her sound: a rich, pearly thing that somehow makes other instruments sound ordinary, even amateurish. Yes, even in this company.

Finally, the act's second scene showcased Dmitri Hvorostovsky (Rodrigo/Posa), whose refined, flamboyant, and long-breathed singing makes quibbles about stamina and power seem petty.

Those are the plusses -- four stars, doing their bit and feeding off each other.

On the other side, surprisingly, is James Levine. He came terrifically to life with Pape and Ramey in Act IV, leaving one to wonder, what was going on before? Aimless and a bit indulgent, the first three acts passed with little of note: even the auto-da-fe barely registered. Odd. (He was on a terrific run of form before his March injury, but maybe it's not coincidence that he's not led a great Levine performance since?)

But the real lesson, I think, is that though Don Carlo(s) can rightly be described as an ensemble opera, it depends heavily on its lead pair to make dramatic sense. The thing is, neither Johan Botha (Carlo himself) nor Patricia Racette (Elisabeth) are actually bad in this. They're just ill suited to their parts and each other.

Botha, as one might remember from Aida, can sing loudly all day long. But he makes nonsense of his character, and of the plot. There are lots of things one might call Carlo: feckless, hapless, immature, in way over his head. But he must be ardent, or the story makes no sense -- for what else could Elisabeth, Rodrigo, and Eboli see in him, and induce them to invest so heavily in his person? It's this side of the character that the restored Fontainebleau scene (Act I, that is) should let shine, but not here. Botha's physical presence is pretty lumbering, yes, but a certain amount of that is forgiveable in opera. But his sense of phrase and rhythm is similarly earthbound, and with facial expressions that range from a smile to a stronger smile, he's got nothing but power with which to win over the listener. No ardor -- of the Italian variety anyway.

With such a partner, maybe I shouldn't blame Racette. But she too seems miscast. She is audible from the bottom to the top of her range, but the top relies heavily on the penetrating timbre of her strong vibrato. It's an ache-filled, almost desperate sound (you can almost feel her melting into the note), perfect for certain things (including her consolation of her attendant, "Non pianger") but impossible in the joy-of-singing romp of the Fontainebleau love duet and, thereafter, jarringly un-regal. Perhaps in compensation, she seems endlessly focussed on holding her body still: whatever the reason, this mostly just makes the performance more remote.

The low-voiced characters of Don Carlo are, unfortunately, satellites in the Carlo/Elisabeth-centered plot. They can't make the whole evening work.

The last revival here had somewhat smaller names -- Radvanovsky, Margison/Villa, d'Intino/Urmana, Croft, Furlanetto, and Burchuladze -- but vivid performances all around, and left one with a sense of the opera's greatness. That this revival leads some to doubt Verdi is depressing.

Monday, December 04, 2006

Rerun

As my comments on tonight's Don Carlo will likely restrict themselves to the performance, please indulge the re-linking of my thoughts on the opera itself, from the time of the last Met revival.

Saturday, December 02, 2006

A leaner, meaner Mozart

Memorable recitals by its Ilia and Idamante made for anticipation for that side of the renewed Met Idomeneo. And there was fire from that quarter. But maybe most memorable on the night was the excellence of a much-maligned singer: soprano Alexandra Deshorties.

I don't think any fan has forgotten the infamous booing incident four years ago, where a heckler was tossed from the Met, apparently for expressing his displeasure with Deshorties during a performance (of Mozart's Abduction). The incident has stuck, in part because the suspicion (fair or no) that the guy might have had it right was never quite dispelled by subsequent outings.

For this reason I was actually surprised to find her still on the Met roster, and maybe she's one of the singers rumored to have been axed by Gelb for future seasons. But however such things may be, it's fortunate that James Levine (or whoever it was) kept engaging her through this Idomeneo.

The technique-in-progress seems finally to have worked itself out, with no pitch issues, odd breaks, or much to complain of past an occasional constriction in the upper register. (Actually, this seemed to afflict a cross-section of the cast this Wednesday.) And what's revealed? A lean, Mozart-weight but hefty voice over a large span, with flexibility and a bite that encourages -- not offends -- the ear. The dramatic sensibility and convincing fire-eating manner were always there, but are sharpened to an amazing point with everything else working. (And it's not just forward motion -- her mad scene was the most uncannily self-aware version of unhinged-ness I've seen, and in the best way.)

Both fast and slow, angry, dreamy, and disintegrating, in this impossible part she was one of the finest Elettras, period. Enough of old stigmas.

* * *

That, obviously, accounts for "meaner". "Leaner" was in the other new principals: Magdalena Kožená and Kobie van Rensburg. Both aurally and... ocularly, they broke unmistakably from their predecessors. The bad? Neither commands the sort of luxuriant sound that Kristine Jepson and Ben Heppner can produce. And Rensburg took stage responsiveness a bit too far, wiggling along to "Fuor del mar" so as to almost spoil his virtuosic account of the music. The good? Everything was quicker, fleeter, more energized. Rensburg isn't a veteran Wagnerian tenor with a huge following, but then again he isn't a tenor who's been singing Wagner for decades and Mozart not in a while. Kožená...

If Hollywood made a movie of Idomeneo, Kožená herself might well be cast as Idamante (beating out Orlando Bloom and Jude Law). It's uncanny how well she fits as the young, impulsive Cretan prince, bright youth against the darker experience of Dorothea Röschmann's Trojan princess Ilia (who is clearly the elder in this incarnation of the relationship). In a sense, it's simple hair-color-coding, but it adds up. Kožená's singing is still not luxuriant -- though the range of sound and color widens over the evening -- but it's dynamic in a way that jolts awake the previously-somnolescent first act, even inspiring Levine. That's not what matters to everyone, and some may find her acting less detailed than Deshorties' or even Röschmann's (the latter is terrific naturally, but given only one note to work with by stage director David Kneuss and the revival crew), but that's to quibble. You have to see her.

I feel I've recently gone over my quota in praise for Dorothea Röschmann, so I'll leave that to Maury this time.

I don't think any fan has forgotten the infamous booing incident four years ago, where a heckler was tossed from the Met, apparently for expressing his displeasure with Deshorties during a performance (of Mozart's Abduction). The incident has stuck, in part because the suspicion (fair or no) that the guy might have had it right was never quite dispelled by subsequent outings.

For this reason I was actually surprised to find her still on the Met roster, and maybe she's one of the singers rumored to have been axed by Gelb for future seasons. But however such things may be, it's fortunate that James Levine (or whoever it was) kept engaging her through this Idomeneo.

The technique-in-progress seems finally to have worked itself out, with no pitch issues, odd breaks, or much to complain of past an occasional constriction in the upper register. (Actually, this seemed to afflict a cross-section of the cast this Wednesday.) And what's revealed? A lean, Mozart-weight but hefty voice over a large span, with flexibility and a bite that encourages -- not offends -- the ear. The dramatic sensibility and convincing fire-eating manner were always there, but are sharpened to an amazing point with everything else working. (And it's not just forward motion -- her mad scene was the most uncannily self-aware version of unhinged-ness I've seen, and in the best way.)

Both fast and slow, angry, dreamy, and disintegrating, in this impossible part she was one of the finest Elettras, period. Enough of old stigmas.

That, obviously, accounts for "meaner". "Leaner" was in the other new principals: Magdalena Kožená and Kobie van Rensburg. Both aurally and... ocularly, they broke unmistakably from their predecessors. The bad? Neither commands the sort of luxuriant sound that Kristine Jepson and Ben Heppner can produce. And Rensburg took stage responsiveness a bit too far, wiggling along to "Fuor del mar" so as to almost spoil his virtuosic account of the music. The good? Everything was quicker, fleeter, more energized. Rensburg isn't a veteran Wagnerian tenor with a huge following, but then again he isn't a tenor who's been singing Wagner for decades and Mozart not in a while. Kožená...

If Hollywood made a movie of Idomeneo, Kožená herself might well be cast as Idamante (beating out Orlando Bloom and Jude Law). It's uncanny how well she fits as the young, impulsive Cretan prince, bright youth against the darker experience of Dorothea Röschmann's Trojan princess Ilia (who is clearly the elder in this incarnation of the relationship). In a sense, it's simple hair-color-coding, but it adds up. Kožená's singing is still not luxuriant -- though the range of sound and color widens over the evening -- but it's dynamic in a way that jolts awake the previously-somnolescent first act, even inspiring Levine. That's not what matters to everyone, and some may find her acting less detailed than Deshorties' or even Röschmann's (the latter is terrific naturally, but given only one note to work with by stage director David Kneuss and the revival crew), but that's to quibble. You have to see her.

I feel I've recently gone over my quota in praise for Dorothea Röschmann, so I'll leave that to Maury this time.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Puppets

The Met ended its run of Madama Butterfly earlier this month, and that I haven't written about it reflects more on the author than the performances. Butterfly usually leaves me indifferent, and did so again this time.

So when I say that Anthony Minghella's production was, if a bit overreceived in its initial press, a big success, you might add salt to taste. His strength was the image: the clean framing and relative boldness of the stage pictures spoke well for his film director's eye. For this alone he'd belong at the Met. The content I found more mixed. Each Act (and he divides Act 2 into Acts 2 and 3, stopping at the Humming Chorus) begins with a short pantomime: some sort of Japanese dancer (Butterfly? who knows), a remembered domestic scene before Pinkerton's departure, and, in the most interesting directorial addition of the night, a dream dance between a puppet Butterfly and (I think -- it's been weeks, I'm afraid) a Japanese-ized Pinkerton. This latter was odd, but affecting; the other additions just seemed extraneous. The puppet Trouble? Eh. Gimmicky, but not bad. At any rate, Minghella definitely deserves a return.

As for the cast... Much has been written about Gallardo-Domas' singing. She doesn't have the vocal heft to win the day on sonic impact, but besides that I found her more than adequate on the occasion. As an actress, she has never been more than generalized, but here she was throwing herself into the rehearsed Japanese-ish gestures with real ferocity. And yet -- they seemed just that, rehearsed gesture, rarely connected to the human and very Italian currents onstage. It seems unfair but I reacted to her much as I did the puppet -- much more grateful, of course, for the intense and sophisticated effort, but still more "huh, that's interesting" than emotional catharsis.

The performance I saw had Dwayne Croft, thankfully, in good voice and better character as Sharpless. Ascher Fisch conducted well, as usual, while it was great misfortune that one of tenor Marcello Giordani's really good nights was wasted on the ungrateful Pinkerton. (The super-variable Giordani seems to be in a good season, though one never can tell with him.)

So when I say that Anthony Minghella's production was, if a bit overreceived in its initial press, a big success, you might add salt to taste. His strength was the image: the clean framing and relative boldness of the stage pictures spoke well for his film director's eye. For this alone he'd belong at the Met. The content I found more mixed. Each Act (and he divides Act 2 into Acts 2 and 3, stopping at the Humming Chorus) begins with a short pantomime: some sort of Japanese dancer (Butterfly? who knows), a remembered domestic scene before Pinkerton's departure, and, in the most interesting directorial addition of the night, a dream dance between a puppet Butterfly and (I think -- it's been weeks, I'm afraid) a Japanese-ized Pinkerton. This latter was odd, but affecting; the other additions just seemed extraneous. The puppet Trouble? Eh. Gimmicky, but not bad. At any rate, Minghella definitely deserves a return.

As for the cast... Much has been written about Gallardo-Domas' singing. She doesn't have the vocal heft to win the day on sonic impact, but besides that I found her more than adequate on the occasion. As an actress, she has never been more than generalized, but here she was throwing herself into the rehearsed Japanese-ish gestures with real ferocity. And yet -- they seemed just that, rehearsed gesture, rarely connected to the human and very Italian currents onstage. It seems unfair but I reacted to her much as I did the puppet -- much more grateful, of course, for the intense and sophisticated effort, but still more "huh, that's interesting" than emotional catharsis.

The performance I saw had Dwayne Croft, thankfully, in good voice and better character as Sharpless. Ascher Fisch conducted well, as usual, while it was great misfortune that one of tenor Marcello Giordani's really good nights was wasted on the ungrateful Pinkerton. (The super-variable Giordani seems to be in a good season, though one never can tell with him.)

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Seeing, hearing, and reading

Australian blogger Pavlov's Cat (whom I found through what appears to be an unrelated spam trackback, but never mind that) has a long, interesting post elaborating some of the memories and associations floating up for her during a recent State Opera of South Australia performance of Nabucco. It's worth a read. (She's no Lieutenant Gustl.)

* * *

It occurred to me during Sunday's Kožená recital that my main experience at a musical performance is of time -- rhythm, breath, tempo and phrase. (At an opera-flavored event, human presence shares the bill.) I hear the sounds distinctly and constantly but as a supporting element, only sporadically prominent (I do focus in at times, mind you, even absent noteworthy display) and mostly carrier rather than itself the headlining content. I'm fairly sure others experience music from the sounds up, and it's interesting how this makes for different reactions to many performers.

* * *

Meanwhile an opera-moderate friend has noted that the endlessly analytic style of this blog rarely takes time to explain terms or background or even what it is exactly I'm describing, making it difficult to grow more opera-fluent via reading.

Now I've tried to gloss more esoteric passing allusions with a link, though I suppose links themselves could come with more regular explanation. But I wonder if other readers are also finding my bouts of concision occasionally overdone, or my words actually jargon-filled.

It occurred to me during Sunday's Kožená recital that my main experience at a musical performance is of time -- rhythm, breath, tempo and phrase. (At an opera-flavored event, human presence shares the bill.) I hear the sounds distinctly and constantly but as a supporting element, only sporadically prominent (I do focus in at times, mind you, even absent noteworthy display) and mostly carrier rather than itself the headlining content. I'm fairly sure others experience music from the sounds up, and it's interesting how this makes for different reactions to many performers.

Meanwhile an opera-moderate friend has noted that the endlessly analytic style of this blog rarely takes time to explain terms or background or even what it is exactly I'm describing, making it difficult to grow more opera-fluent via reading.

Now I've tried to gloss more esoteric passing allusions with a link, though I suppose links themselves could come with more regular explanation. But I wonder if other readers are also finding my bouts of concision occasionally overdone, or my words actually jargon-filled.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

Idomeneites