The New York Times' Anthony Tommasini seems to be getting a fair amount of stick these days -- some of it warranted, but do you folks remember his predecessors!? -- but this article returns to one of his most admirable moments: the long crusade against City Opera's electronic "enhancement".

As he originally predicted, miking has slowly gotten more obvious and widespread since that first crack of the door. (Most notable here: that loved-by-theater-critics, trashed-by-opera-folks (amplified) run of Luhrmann's Boheme.)

What he doesn't mention this time, though the article appears in IHT, is that it's not just an American issue: a growing number of European venues has been using electronic sound sweetener as well, including the Berlin State Opera. Does the local press there even mention this sort of thing?

In my New York experience, City Opera's sound system is often the least of its problems, though use sometimes verges on the abusive, while BAM abuses its version quite a lot. The Met, of course, remains fairly purist -- though a pessimist might wonder what Gelb has in store.

UPDATE (1:45AM): It appears the Met isn't always purist enough. Perhaps they've been taking too much advice from Barbara Cook?

UPDATE 2 (3AM): This wouldn't be a bad place for FTC or its state equivalents to mandate full (or at least pretty substantial) disclosure. Any consumer advocate types out there? (Perhaps throwing in pop lipsynching disclosure would get the ball moving...)

Saturday, December 31, 2005

Thursday, December 29, 2005

On applause

A year ago I posted a taxonomy of opera experience, primarily as a tool for understanding how others might strongly approve -- or disapprove -- of a performance one does not. For sometimes it's disagreement about a specific thing, but as often we talk past each other, each looking to parts of the evening the other discounts.

A post months later picked up that thread a little, beginning to examine live performance v. transmission/recording in light of this taxonomy. But continuing seemed a bit redundant, as simply listing the aspects of operatic experience previously noted pretty much makes the distinctions, trivial and not, apparent:

But those mikes at a non-broadcast performance of American Tragedy got me thinking about this again. Was that evening particularly focused because (and again, I was just speculating as to why the mikes were there) the event was to be recorded? Such things happen. Performers improve, or tighten up, or something with such a prospect. And it's odd: the dynamic among performers and audience -- the dramatic element of theater, in this case opera -- is changed by listeners who, not being in fact present (or in some cases even yet existing), cannot physically affect the show in any way, whether by breathing, squirming, coughing, rustling, talking, clapping, cheering, booing, or sitting blessedly still. Their presence in performers' minds seems sufficient.

Yet for the home listener, much of the drama is washed out -- secondhand. Sound and video may preserve some of the energy exchanged and transformed there among those present, but even then they offer no personal way in. The presence of the distant audience was a collective one, its individual parts hardly differentiated in that sea of (at best) invisible imagined reaction. Did that in-house audience imagine this remote listener too? Sit rapt, cheer, or boo on his behalf? He himself is impossibly distant, and can't.

* * *

Of these missing interjections, applause is the key. It's the consummation of performance-as-drama, the Dionysian end of the rite. (And those who would "encourage" it in the guise of opposing classical "stuffiness" bark up entirely the wrong tree.) Each listener there (heretofore officially passive) has a share of the revels, perhaps some share of the performers themselves... But the solitary listener at home does not. His circle doesn't close so neatly; any energy and tension and approval and resentment aroused in the event isn't so easily dissipated. (Fortunately, then, these usually aren't as great.)

What, then? Why -- words. Talk, online chat, IM exchanges, review missives to electronic fora, "best of" lists, fan sites, and, yes, sometimes blog posts and blog comments. Reading and writing both.

Of course, I say this on a blog mostly inspired by local live performance...

A post months later picked up that thread a little, beginning to examine live performance v. transmission/recording in light of this taxonomy. But continuing seemed a bit redundant, as simply listing the aspects of operatic experience previously noted pretty much makes the distinctions, trivial and not, apparent:

(1) Opera is a sensual art.Really I have no patience for systems, even my own.

(2) Opera is a dramatic art.

(3) Opera illuminates the world, and one's experience in it.

(4) Opera illuminates its own world: the history, present, and future of opera.

(5) Operagoing is a social activity, beyond and around the sitting-in-the-dark-as-an-audience part.

But those mikes at a non-broadcast performance of American Tragedy got me thinking about this again. Was that evening particularly focused because (and again, I was just speculating as to why the mikes were there) the event was to be recorded? Such things happen. Performers improve, or tighten up, or something with such a prospect. And it's odd: the dynamic among performers and audience -- the dramatic element of theater, in this case opera -- is changed by listeners who, not being in fact present (or in some cases even yet existing), cannot physically affect the show in any way, whether by breathing, squirming, coughing, rustling, talking, clapping, cheering, booing, or sitting blessedly still. Their presence in performers' minds seems sufficient.

Yet for the home listener, much of the drama is washed out -- secondhand. Sound and video may preserve some of the energy exchanged and transformed there among those present, but even then they offer no personal way in. The presence of the distant audience was a collective one, its individual parts hardly differentiated in that sea of (at best) invisible imagined reaction. Did that in-house audience imagine this remote listener too? Sit rapt, cheer, or boo on his behalf? He himself is impossibly distant, and can't.

Of these missing interjections, applause is the key. It's the consummation of performance-as-drama, the Dionysian end of the rite. (And those who would "encourage" it in the guise of opposing classical "stuffiness" bark up entirely the wrong tree.) Each listener there (heretofore officially passive) has a share of the revels, perhaps some share of the performers themselves... But the solitary listener at home does not. His circle doesn't close so neatly; any energy and tension and approval and resentment aroused in the event isn't so easily dissipated. (Fortunately, then, these usually aren't as great.)

What, then? Why -- words. Talk, online chat, IM exchanges, review missives to electronic fora, "best of" lists, fan sites, and, yes, sometimes blog posts and blog comments. Reading and writing both.

Of course, I say this on a blog mostly inspired by local live performance...

Monday, December 26, 2005

Reception

The December 16 performance of An American Tragedy had another interesting novelty to it: large visible mikes at the foot of the stage. Usually (I think) these are only present for broadcasts, and I wonder if this means an official audio recording will be forthcoming. (There were no official cameras.) With the apparently universal technical glitches in Saturday's broadcast Act 2 -- not to mention widespread preemption in favor of dull Christmas-music specials -- a cleaner official document would be welcome. It could also, if the approval ratio of Opera-L commenters is any indication, help tap a strong potential audience.

As for the broadcast itself, I heard only Act 1 -- though I very much wish I'd caught the artists' roundtable. Still, as each time before, Picker's music insinuated itself into my brain, replaying in fragments afterwards late into the night and prompting an itch to be heard, in flesh, again. That, I suppose, is the bottom line of my piecemeal takes on his contribution, and not the worst way to conclude them.

As for the broadcast itself, I heard only Act 1 -- though I very much wish I'd caught the artists' roundtable. Still, as each time before, Picker's music insinuated itself into my brain, replaying in fragments afterwards late into the night and prompting an itch to be heard, in flesh, again. That, I suppose, is the bottom line of my piecemeal takes on his contribution, and not the worst way to conclude them.

Saturday, December 24, 2005

Unwrapping

My friend and blogdaughter Victoria seems to have given me the neatest Christmas present: a graphic (non-representational, mind you) and bit of ad space on her blog. Thanks, Vic. And welcome to any and all of her readers who are now dropping by.

And to all my readers, old and new -- merry Christmas, happy Hanukkah, and all that.

And to all my readers, old and new -- merry Christmas, happy Hanukkah, and all that.

Three takes

I spent three consecutive weeks (Friday, Thursday, Friday) at performances of An American Tragedy; each showed the piece as a different thing. Opening night was remarkable, but perhaps the best evening was last Friday's. Star Susan Graham was indisposed, replaced by her cover Kirsten Chavez, but that was little problem on the whole. Chavez has a smoother, less punchy top, a meltingly appealing lower register, and a more straightforwardly youthful stage demeanor than her predecessor. In Chavez's body Sondra Finchley is more Clyde Griffiths' eager co-dreamer than an ideal, composed focus of desire -- but that works too, and perhaps put attention more comfortably on the protagonist. Even in today's sea of excellent mezzos, I'd like to hear her again.

Meanwhile Nathan Gunn, I think, has gotten bad press. His voice actually shows well in the part: the only thing he lacks are the climactic high notes called for in the car aria. Unfortunately, these stick out.

* * *

Perhaps closest kin to Clyde as an operatic protagonist is Lulu: each navigates a social rise and fall, bisected by murder. Lulu inspires desire while Clyde is its agent, but the effect of each on others reveals society and drives the plot.

Tobias Picker acknowledges it early, beginning the first latter-day scene with a nod to Berg's most beautiful of all operas, both orchestrally and in the difficult (and oddly maligned) vocal line of small-time seductress Hortense. But then all sorts of other stuff rushes in -- each character, as the official interview noted, gets not a leitmotif but a characteristic style -- adding up to a more heterogenous whole than Lulu's beauty-plus-corruption-plus-death. Is it, I wonder, the fracturing of this equation that's bothered critics? The loveliness of Lulu's sound must, no less than her person's, be paid with violence. Conlon's Friday account happily brought this element of An American Tragedy out more than before, but there's nothing in the score that approximates the violence of, say, Berg's central interlude. Instead -- everything else. And then savaging -- in ink.

* * *

Noted: two music-journalism professionals who've admitted to liking the new piece are blog proprietors. Meanwhile, the local doyen of opera criticism offers yet another by-the-book trashing of Picker's work.

Don't ask me what that means, though.

Meanwhile Nathan Gunn, I think, has gotten bad press. His voice actually shows well in the part: the only thing he lacks are the climactic high notes called for in the car aria. Unfortunately, these stick out.

Perhaps closest kin to Clyde as an operatic protagonist is Lulu: each navigates a social rise and fall, bisected by murder. Lulu inspires desire while Clyde is its agent, but the effect of each on others reveals society and drives the plot.

Tobias Picker acknowledges it early, beginning the first latter-day scene with a nod to Berg's most beautiful of all operas, both orchestrally and in the difficult (and oddly maligned) vocal line of small-time seductress Hortense. But then all sorts of other stuff rushes in -- each character, as the official interview noted, gets not a leitmotif but a characteristic style -- adding up to a more heterogenous whole than Lulu's beauty-plus-corruption-plus-death. Is it, I wonder, the fracturing of this equation that's bothered critics? The loveliness of Lulu's sound must, no less than her person's, be paid with violence. Conlon's Friday account happily brought this element of An American Tragedy out more than before, but there's nothing in the score that approximates the violence of, say, Berg's central interlude. Instead -- everything else. And then savaging -- in ink.

Noted: two music-journalism professionals who've admitted to liking the new piece are blog proprietors. Meanwhile, the local doyen of opera criticism offers yet another by-the-book trashing of Picker's work.

Don't ask me what that means, though.

Monday, December 19, 2005

Quiet

After an amazingly hectic weekend that kept me from hearing the season's first broadcast, I'm off to an opera-free zone until the new year. I've another report on An American Tragedy planned, but I'll miss upcoming New York events in those weeks.

I hope to finish some reflective posts instead, but such things aren't always predictable. Please bear with me.

I hope to finish some reflective posts instead, but such things aren't always predictable. Please bear with me.

Friday, December 16, 2005

Blogout

The transit strike hasn't quite happened here, but in internet-land Six Apart's servers -- which host the blogs at blogs.com and typepad.com -- did get toasted.

If Prima la Musica, vilaine fille, and Night After Night look like they've been replaced by slightly-out-of-date mute plastic replicas, it's pretty much true. And there's as yet no immediate prospect of recovery.

UPDATE (12/17, 12:10AM): Things look in order again.

If Prima la Musica, vilaine fille, and Night After Night look like they've been replaced by slightly-out-of-date mute plastic replicas, it's pretty much true. And there's as yet no immediate prospect of recovery.

UPDATE (12/17, 12:10AM): Things look in order again.

Empty seat syndrome

Via Opera-L, this AP story puts a remarkably bad number to the vague local perception of "low box office":

(The sold-out Rigoletto aside, the only thing I've been to of late has been An American Tragedy. That seemed pretty full on both occasions, but I now wonder how much of it was paper.)

Incoming general manager Peter Gelb's instinct seems to be to up the stakes with more and trendier new productions. Is this, I wonder, a pitch for the local market or for the transatlantic one depressed since 9/11?

"We are currently projecting the box office to achieve 76 percent of capacity versus a budget of 80 percent, resulting in a shortfall of $4,303,000," Volpe wrote in Dec. 12-dated memorandum to Met department heads, a copy of which was obtained Thursday by The Associated Press.76 percent! And in a boom year, with good casting.

(The sold-out Rigoletto aside, the only thing I've been to of late has been An American Tragedy. That seemed pretty full on both occasions, but I now wonder how much of it was paper.)

Incoming general manager Peter Gelb's instinct seems to be to up the stakes with more and trendier new productions. Is this, I wonder, a pitch for the local market or for the transatlantic one depressed since 9/11?

Wednesday, December 14, 2005

Einsam, wie eine Wolke

Schubert's Winterreise begins with a scenic specificity as strong as any opera's: the place and landmarks of one now-lost love. As much as they torment the protagonist, and as intently as he flees that scene, he is stuck close among them for much of the cycle's first half (written as a unit by Schubert before he discovered the rest of Müller's opus). This immediacy asks for viscerally dramatic realization, and it is here that a stage star like Peter Anders can really shine.

Christoph Prégardien, who sang the whole piece at Alice Tully Hall on Sunday, is a lightish (though now darker-sounding) tenor without that operatic breadth of vocal resource. This was a handicap at the start: the first songs' rage and sorrow were dulled by Prégardien's apparent need to manage sonic and emotional extremes instead of exploiting them. (This is, I think, the gist of Maury's complaint about Guelfi's Rigoletto.) So maybe it wasn't so bad that the hall's fire alarm went off not once but twice -- water pressure in another building, went the official explanation -- causing Prégardien and his straightforward accompanist Dennis Helmrich to walk offstage after "Auf dem Flusse".

They came back to applause and a song or two of nervous unsteadiness, but soon reached a more congenial point. For the hero does escape love's immediate pangs -- this is the motion of that first half-cycle. Eventually, he puts sleep between them... and from then his personal history is reflected in ever more distant metaphor (in the ever more empty world), until pared down to a missing pair of suns. In this less overtly dramatically-strenuous part of the cycle Prégardien excelled, beginning with an unhysterical but wholly effective "Frülingstraum". The disillusioning shock of awakening, the hope-draining return to cold -- these seemed as if for the first time experienced plainly, by one inclined neither to expect more nor complain.

Perceptive simplicity served Prégardien well through the very tricky final songs. His wanderer, with distance from the sharp reactions of love -- and everything else! -- showed himself human and truthful: not, as is a danger, emptily overblown. So if Prégardien, like Wordsworth, needs a bit of admixed tranquility to best show his emotional art, it seems petty to complain.

Christoph Prégardien, who sang the whole piece at Alice Tully Hall on Sunday, is a lightish (though now darker-sounding) tenor without that operatic breadth of vocal resource. This was a handicap at the start: the first songs' rage and sorrow were dulled by Prégardien's apparent need to manage sonic and emotional extremes instead of exploiting them. (This is, I think, the gist of Maury's complaint about Guelfi's Rigoletto.) So maybe it wasn't so bad that the hall's fire alarm went off not once but twice -- water pressure in another building, went the official explanation -- causing Prégardien and his straightforward accompanist Dennis Helmrich to walk offstage after "Auf dem Flusse".

They came back to applause and a song or two of nervous unsteadiness, but soon reached a more congenial point. For the hero does escape love's immediate pangs -- this is the motion of that first half-cycle. Eventually, he puts sleep between them... and from then his personal history is reflected in ever more distant metaphor (in the ever more empty world), until pared down to a missing pair of suns. In this less overtly dramatically-strenuous part of the cycle Prégardien excelled, beginning with an unhysterical but wholly effective "Frülingstraum". The disillusioning shock of awakening, the hope-draining return to cold -- these seemed as if for the first time experienced plainly, by one inclined neither to expect more nor complain.

Perceptive simplicity served Prégardien well through the very tricky final songs. His wanderer, with distance from the sharp reactions of love -- and everything else! -- showed himself human and truthful: not, as is a danger, emptily overblown. So if Prégardien, like Wordsworth, needs a bit of admixed tranquility to best show his emotional art, it seems petty to complain.

Monday, December 12, 2005

One

The blog is a year old today, though perhaps it really began two days later with my contrarian take on Rodelinda.

Thanks to all of you for reading. Particular thanks to Sarah, whom I believe the first blogger to link here, and to my friends Victoria and "Maury", who by starting their own blogs have provided incalculable continuing encouragement.

Thanks to all of you for reading. Particular thanks to Sarah, whom I believe the first blogger to link here, and to my friends Victoria and "Maury", who by starting their own blogs have provided incalculable continuing encouragement.

Sunday, December 11, 2005

By comparison...

She performs with the widened sonic and gestural vocabulary of a master, though she isn't one yet. She has every note from bottom to top, and a not-bad trill. She is beautiful, and has a good sense of what she should be doing at any particular moment onstage. So who am I to complain that Anna Netrebko's voice is not now the glowing silver peal of 1998 (the year depicted at right), nor even the (darker) burnished steel of 2002? Someone who heard and liked those incarnations, I guess. Today the sound is remarkably large for her type, still clear, and easily produced, but no longer has the immediate sensual allure of years past. In fact she's starting to sound like another east-Euro beauty -- Angela Gheorghiu (a younger one, anyway, with an easier top) -- which makes some sense since their roles are beginning to converge. Perhaps their stardom already has.

So who am I to complain that Anna Netrebko's voice is not now the glowing silver peal of 1998 (the year depicted at right), nor even the (darker) burnished steel of 2002? Someone who heard and liked those incarnations, I guess. Today the sound is remarkably large for her type, still clear, and easily produced, but no longer has the immediate sensual allure of years past. In fact she's starting to sound like another east-Euro beauty -- Angela Gheorghiu (a younger one, anyway, with an easier top) -- which makes some sense since their roles are beginning to converge. Perhaps their stardom already has.

By contrast Rolando Villazón's basic sound may be his strongest asset: the quick vibrato makes much more sound urgent, heartfelt. But his slim good looks and youthful bounding and phrasing help, and it's topped off by remarkable and effortless-seeming resources of breath. The voice is really expansive in the middle, but ordinary on top -- sort of a mini-dramatic's instrument.

The last act of Saturday's season-first Met Rigoletto showcased both the ups and downs of Villazón's sonic endowment. "La donna è mobile" made little impression, brought down by dull high notes and an uncharacteristic bout of chronic flatting. But the quartet, with Villazón spinning easy, ardent, never-ending phrases -- that was something.

His Duke is a youth, not a man: confident but quick-moving, impulsive, jumping from one thing to another (and, unfortunately, chopping phrases in the process), his fatal callousness more adolescent self-regard than narcissism or sociopathy. Phrase-chopping aside, I suppose it's a reasonable take. Surely it's not much Villazón's fault that I found myself craving another tenor's stage persona in the part...

The title part was sung well -- if neither overpoweringly nor with much mad frenzy -- by Carlo Guelfi. But the real protagonist of the night was conductor Asher Fisch. He (almost as well as Robert Heger in my favorite Rigoletto recording) liberates all the forward rhythms of the opera, midwifing an exhilarating Verdian performance that certainly won't happen under the worst conductor in Met history. Eric Halfvarson is strong, while Nancy Fabiola Herrera, though irritatingly behind the beat for the night's quartet, has a nice rounded sound. With Fisch's guidance and no weak links in the cast, Rigoletto is a success... even if not ideal.

UPDATE (11:55 AM): Alex's review at Wellsung reminds me of one thing I omitted -- the excellent work of the chorus. They, James Courtney as Monterone, and the other bit-player courtiers made the opening scene really riveting. The Met Orchestra's excellence should go without saying.

So who am I to complain that Anna Netrebko's voice is not now the glowing silver peal of 1998 (the year depicted at right), nor even the (darker) burnished steel of 2002? Someone who heard and liked those incarnations, I guess. Today the sound is remarkably large for her type, still clear, and easily produced, but no longer has the immediate sensual allure of years past. In fact she's starting to sound like another east-Euro beauty -- Angela Gheorghiu (a younger one, anyway, with an easier top) -- which makes some sense since their roles are beginning to converge. Perhaps their stardom already has.

So who am I to complain that Anna Netrebko's voice is not now the glowing silver peal of 1998 (the year depicted at right), nor even the (darker) burnished steel of 2002? Someone who heard and liked those incarnations, I guess. Today the sound is remarkably large for her type, still clear, and easily produced, but no longer has the immediate sensual allure of years past. In fact she's starting to sound like another east-Euro beauty -- Angela Gheorghiu (a younger one, anyway, with an easier top) -- which makes some sense since their roles are beginning to converge. Perhaps their stardom already has.By contrast Rolando Villazón's basic sound may be his strongest asset: the quick vibrato makes much more sound urgent, heartfelt. But his slim good looks and youthful bounding and phrasing help, and it's topped off by remarkable and effortless-seeming resources of breath. The voice is really expansive in the middle, but ordinary on top -- sort of a mini-dramatic's instrument.

The last act of Saturday's season-first Met Rigoletto showcased both the ups and downs of Villazón's sonic endowment. "La donna è mobile" made little impression, brought down by dull high notes and an uncharacteristic bout of chronic flatting. But the quartet, with Villazón spinning easy, ardent, never-ending phrases -- that was something.

His Duke is a youth, not a man: confident but quick-moving, impulsive, jumping from one thing to another (and, unfortunately, chopping phrases in the process), his fatal callousness more adolescent self-regard than narcissism or sociopathy. Phrase-chopping aside, I suppose it's a reasonable take. Surely it's not much Villazón's fault that I found myself craving another tenor's stage persona in the part...

The title part was sung well -- if neither overpoweringly nor with much mad frenzy -- by Carlo Guelfi. But the real protagonist of the night was conductor Asher Fisch. He (almost as well as Robert Heger in my favorite Rigoletto recording) liberates all the forward rhythms of the opera, midwifing an exhilarating Verdian performance that certainly won't happen under the worst conductor in Met history. Eric Halfvarson is strong, while Nancy Fabiola Herrera, though irritatingly behind the beat for the night's quartet, has a nice rounded sound. With Fisch's guidance and no weak links in the cast, Rigoletto is a success... even if not ideal.

UPDATE (11:55 AM): Alex's review at Wellsung reminds me of one thing I omitted -- the excellent work of the chorus. They, James Courtney as Monterone, and the other bit-player courtiers made the opening scene really riveting. The Met Orchestra's excellence should go without saying.

Saturday, December 10, 2005

Attention

Though I began this blog by calling opera exemplary, few people actually wish to live -- or, perhaps more to the point, die -- like their favorite operatic hero(ine). Even among singers. Though it's a change from norms set back when life expectancy was around 30, the training and hiring system today more than ever tries to protect singers, bringing them along slowly into (ideally) a long career -- one which might start at an age by which a performer of yore could already have blown out his voice.

(Some have wondered if this has inhibited the tragic vein in modern well-trained singers. That seems to me to confuse cause and effect: we live longer, and take steps based on living longer, because we have -- collectively -- largely adopted a less tragic approach to life. Besides making us rich and healthy, this choice has colored other things, moving the norm from which an individual -- performer or no -- is likely to start.)

But no system can -- or would wish to -- hide the fact that the stage is an essentially dangerous, precarious place. Like a prophet or tyrant of old, the performer is the focus of mass attention, and is in turn subject to its often-resentful whims. (One remembers how many of those prophets and tyrants ended.) This is the raw dramatic energy of opera performance: tragedy channels it into awful terrors for the characters, comedy into laughter at their folly. So each night these fictional constructs pay for their performers' prominence, freeing us in the audience to marvel at the athletic, mimetic, and other skills well-displayed. But if something goes wrong... And even when it doesn't, surely some must wonder if the substitution's something that can be carried off indefinitely, or if the real person will eventually have to pay...

Some performers live tragic lives, others are clowns (amusing or detestable), and very many live straightforwardly while off the job. Most, I think, prefer the latter -- as would most of us. (Others take part in celebrity, that satyr play-cum-romance that's the essence of popular culture, but that's tricky -- and not an aspect that shows much while in the high-cultural repertory of staged opera. For TV and concerts and miscellaneous appearances, yes.)

* * *

Blogging, too, is perilous -- hardly as much, but in much the same way, though many further deflect attention with a pseudonym. And while most don't necessarily read blogs for the dramatic one-before-many aspect, it is there, even sans applause, booing, or even fan/hate mail.

If one has even blogged himself towards death (though he's still around at the moment), that shows an outer limit to dedication -- and its possible cost. It, too, lets in that damned demanding, troublesome thing: the public eye.

So when a favorite blogger -- only thinly pseudonymous and, at the same time, a nearly-famous soprano -- goes on hiatus feeling "overexposed", shouldn't all bloggers sympathize? Even if their attention fed the performer-side aspect of the condition in the first place, and even if writing about it may feed it all even more.

(Another soprano offers her thoughts on blogging here.)

(Some have wondered if this has inhibited the tragic vein in modern well-trained singers. That seems to me to confuse cause and effect: we live longer, and take steps based on living longer, because we have -- collectively -- largely adopted a less tragic approach to life. Besides making us rich and healthy, this choice has colored other things, moving the norm from which an individual -- performer or no -- is likely to start.)

But no system can -- or would wish to -- hide the fact that the stage is an essentially dangerous, precarious place. Like a prophet or tyrant of old, the performer is the focus of mass attention, and is in turn subject to its often-resentful whims. (One remembers how many of those prophets and tyrants ended.) This is the raw dramatic energy of opera performance: tragedy channels it into awful terrors for the characters, comedy into laughter at their folly. So each night these fictional constructs pay for their performers' prominence, freeing us in the audience to marvel at the athletic, mimetic, and other skills well-displayed. But if something goes wrong... And even when it doesn't, surely some must wonder if the substitution's something that can be carried off indefinitely, or if the real person will eventually have to pay...

Some performers live tragic lives, others are clowns (amusing or detestable), and very many live straightforwardly while off the job. Most, I think, prefer the latter -- as would most of us. (Others take part in celebrity, that satyr play-cum-romance that's the essence of popular culture, but that's tricky -- and not an aspect that shows much while in the high-cultural repertory of staged opera. For TV and concerts and miscellaneous appearances, yes.)

Blogging, too, is perilous -- hardly as much, but in much the same way, though many further deflect attention with a pseudonym. And while most don't necessarily read blogs for the dramatic one-before-many aspect, it is there, even sans applause, booing, or even fan/hate mail.

If one has even blogged himself towards death (though he's still around at the moment), that shows an outer limit to dedication -- and its possible cost. It, too, lets in that damned demanding, troublesome thing: the public eye.

So when a favorite blogger -- only thinly pseudonymous and, at the same time, a nearly-famous soprano -- goes on hiatus feeling "overexposed", shouldn't all bloggers sympathize? Even if their attention fed the performer-side aspect of the condition in the first place, and even if writing about it may feed it all even more.

(Another soprano offers her thoughts on blogging here.)

Wednesday, December 07, 2005

A composer responds (in advance)

I'd read this 2001 interview with Tobias Picker before the production, but it's more funny now:

In the '60s and '70s when American modernism was at its height, when 12-tone composers were chic, the critics bashed the shit out of them because they were writing music that was inaccessible. There was a constant stream of vicious criticism and harassment, led by Harold Schonberg and the critics of The New York Times, directed toward my teachers, Elliott Carter, Milton Babbitt and Charles Wourinen, who were leaders of the American modernist movement. This has now turned full circle. As soon as composers started writing music that was accessible, the critics starting bashing the shit out of us. It proves that some critics will find no good in anything, and this basically renders most music criticism meaningless.UPDATE (5:30 AM): Composer-blogger Daniel Felsenfeld asks a related (if more restrained) question.

The very busy...

I hadn't realized that An American Tragedy's younger Clyde, Graham Phillips, was also the lead for half of NYCO's run of The Little Prince (closed 11/20). Not a bad few months' work for a sixth-grader.

The current show uses his actual voice. I'm sure it's a stretch to expect a child to sing for the hours' length of Little Prince -- even on and off -- but NYCO's solution of massive (by opera-house standards), jarringly different-sounding amplification really made a mess of that production. Surely it wasn't quite so bad in Houston? (The unwise innovation of this time casting the Rose as a teenage soprano meant they did much the same for her.) But I suspect I'm the only one grinch enough to so complain, though Peter Davis does trash most everything else.

Meanwhile, if any readers went to this American Tragedy event yesterday, I'm curious to learn what was said.

The current show uses his actual voice. I'm sure it's a stretch to expect a child to sing for the hours' length of Little Prince -- even on and off -- but NYCO's solution of massive (by opera-house standards), jarringly different-sounding amplification really made a mess of that production. Surely it wasn't quite so bad in Houston? (The unwise innovation of this time casting the Rose as a teenage soprano meant they did much the same for her.) But I suspect I'm the only one grinch enough to so complain, though Peter Davis does trash most everything else.

Meanwhile, if any readers went to this American Tragedy event yesterday, I'm curious to learn what was said.

Tuesday, December 06, 2005

Press roundup

I think Alex of the Wellsungs is entirely right to dissect Tommasini's reflexive and cliched dismissal of An American Tragedy. One further point I'd add: 1950 is just as much unrecoverable past today as is 1905 or 1850. A rearguard defense of modernism won't turn back the clock from its aesthetic successors.

Oh, but who has the space to do justice to the riotous melange of honest opinion, grinding axes, insight, generalization, quick conclusions, and bizarre hobbyhorses that makes up the rest of the press coverage? It almost takes one back to the delightful old days before hundreds of years of noisy fan appreciation forced critics to dress their hatreds in polite language.

Most amusing, I think, is the pair of Jay Nordlinger and Willa Conrad, who each attribute the rather more lugubrious political agenda of Dreiser's book to the opera, to opposite ends: Nordlinger deplores it, which seems to dim his view of the rest of the proceedings, while Conrad pretty much finds it the only element of the evening worth keeping.

Of the others, only the AP's Mike Silverman gives a mixed evaluation. The remainder trash it, with more or less style. Of these, I think Matthew Erikson of the Hartford Courant is the most interesting and grandees Martin Bernheimer and Clive Barnes the least. Mark Swed of the LA Times (who, incomprehensibly, liked the Harbison fiasco!) offers another ideological attack, while Newsday's Justin Davidson and Variety's Eric Myers just found the show dull. (Oddly, the latter give no report of the -- contrary -- audience reaction.)

Your milage, needless to say, may vary. This is definitely an instance where one should see for oneself.

UPDATE (12:20 PM): OK, maybe the Wellsungs are up to fisking the whole lot of 'em. Jonathan's funny take on Eric Myers here.

UPDATE 2 (12/7, 3:30 AM): More ink -- Chicago's John von Rhein, though quite fair-minded on the whole, wishes LOC's composer William Bolcom had written it (having seen A View from the Bridge, I don't), while Charles Ward of the Houston Chronicle does his own press roundup.

UPDATE 3 (12/8): A positive review from the Philadelphia Inquirer's David Patrick Stearns.

Oh, but who has the space to do justice to the riotous melange of honest opinion, grinding axes, insight, generalization, quick conclusions, and bizarre hobbyhorses that makes up the rest of the press coverage? It almost takes one back to the delightful old days before hundreds of years of noisy fan appreciation forced critics to dress their hatreds in polite language.

Most amusing, I think, is the pair of Jay Nordlinger and Willa Conrad, who each attribute the rather more lugubrious political agenda of Dreiser's book to the opera, to opposite ends: Nordlinger deplores it, which seems to dim his view of the rest of the proceedings, while Conrad pretty much finds it the only element of the evening worth keeping.

Of the others, only the AP's Mike Silverman gives a mixed evaluation. The remainder trash it, with more or less style. Of these, I think Matthew Erikson of the Hartford Courant is the most interesting and grandees Martin Bernheimer and Clive Barnes the least. Mark Swed of the LA Times (who, incomprehensibly, liked the Harbison fiasco!) offers another ideological attack, while Newsday's Justin Davidson and Variety's Eric Myers just found the show dull. (Oddly, the latter give no report of the -- contrary -- audience reaction.)

Your milage, needless to say, may vary. This is definitely an instance where one should see for oneself.

UPDATE (12:20 PM): OK, maybe the Wellsungs are up to fisking the whole lot of 'em. Jonathan's funny take on Eric Myers here.

UPDATE 2 (12/7, 3:30 AM): More ink -- Chicago's John von Rhein, though quite fair-minded on the whole, wishes LOC's composer William Bolcom had written it (having seen A View from the Bridge, I don't), while Charles Ward of the Houston Chronicle does his own press roundup.

UPDATE 3 (12/8): A positive review from the Philadelphia Inquirer's David Patrick Stearns.

Monday, December 05, 2005

An American story

Class is not today one of the more salient factors in American life, but in New York*? -- that's another story. Class awareness and envy is a popular local bloodsport, which fact colors not only local media (New York magazine is the most prominent of those pretty much entirely dedicated to scratching this itch) but national press coverage (which takes its cues from the Times and other locals).

Of course, there's more to it than that. Clyde Griffiths isn't felled by class conflict, after all, nor even by the consumer hunger (the opera gives Clyde this aria soon after arriving in Lycurgus) that pushes him into it. It's a more universal aspect of his charmingly unbanked desire* that brings him to ruin: love, or lust. In this it follows the novel's famous movie adaptation, A Place in the Sun, perhaps more closely than one might have expected. As in that version, Clyde's desire for worldly advancement is embodied -- maybe even subsumed -- by his desire for the alluring, possibility-intoxicated Sondra Finchley, who as perfectly written for Susan Graham (think of her Hahn album, not Octavian) becomes a fairly understandable motive for unfaithfulness. But this, too -- like Clyde's seduction and abandonment of the less colorful Roberta Alden -- is a familiar local story as much as a universal one.

* * *

The first act -- there are two, each about an hour and a quarter -- rushes forward breathlessly; the second builds, with much contemplative breath at the beginning, to a gripping dramatic climax (and a lone plunk). The seamless scene-to-scene changes of each are enabled by Adrianne Lobel's excellent three-tiered set design, with two levels for action (some simultaneous in two times or places) and the top for complementary scenery. Painted panels slide across the three levels, and combine with occasional solid slide-on set elements to form a great range of stage images. It's a production that takes good advantage of the Met's size and stage apparatus, and might be tricky to put on elsewhere.

changes of each are enabled by Adrianne Lobel's excellent three-tiered set design, with two levels for action (some simultaneous in two times or places) and the top for complementary scenery. Painted panels slide across the three levels, and combine with occasional solid slide-on set elements to form a great range of stage images. It's a production that takes good advantage of the Met's size and stage apparatus, and might be tricky to put on elsewhere.

In a sense the drama recapitulates -- as do its somewhat greater forerunners -- the story of its creators' civilization. Act I, moving ceaselessly forward from scene to ever-shifting scene, is entirely Clyde's -- which is to say desire's. Its unbanked force within him, manifesting in characteristically American form (as above), conquers what's before it, triggering and feeding from desires of those around him. So Clyde gets his job, then his woman, then his social entree, while Roberta finds love and Sondra -- who has discovered desire herself in New York (not least, of course, through its consumer opportunities!) -- a playmate and co-dreamer.

These, naturally, can't all coexist -- a far more fundamental problem for Clyde (and society) than the mean-but-incidental snobbery of his cousin or aunt. Act I closes with his idyll of ever-newly-satisfied desires being fatally cracked, as Roberta tells him she is pregnant.

But Clyde doesn't follow the rules that would have him resolve these conflicting desires at the point where their conflict has been unmistakably spotlit. This begins Act II's crime-and-punishment structure. He lets things fester, delusionally (or sociopathically) believing that he can still have everything, notwithstanding others' claims. Against this belief every society must defend itself (as also here), not least because it moves some to kill. For Clyde it's a letting-die, though the legal machinery by which peace in America is kept -- even against the strong sexual and economic passions of the country, this incubator of Act I's desire -- finds him a murderer. Whatever the niceties, Clyde's personal case resolves when he acknowledges to his mother that his inner guilt matches the outer. The transgression that began the act thus ends.

* * *

Of Picker's music one might make many complaints fair and unfair, but we should first start with this: it well suits the text and performers of the piece. Picker, at the least, well and correctly judged the dramatic arc of the story and the vocal/character possibilities of the people who were to embody it. Beyond that, my initial general impression was that none of it is boring, but too much of it falls into the slow-rapt and fast-ominous dichotomy that's been too common for too long. (What I miss most in new operas is the cabaletta.)

One might joke about the music being set in 1906, as well as the story -- Picker seems to look more to Janáček than to any critically-approved living composer -- but my main thought at the end was: good, now commission from them another one.

More on this, perhaps, after more hearings.

* * *

Finally, no one familiar with singing today should be surprised that the two star-quality instruments in the production are both mezzos, and that they walk away with the performance side of the show. Susan Graham and Dolora Zajick's considerable vocal and temperamental talents are shown off very, very well by their parts. Patricia Racette provides blood aplenty to the veins of Roberta, but -- as hinted above -- not a lot of extra color to her character. (It would take a Lucrezia Bori to add that.) In the lead, Nathan Gunn embodies Clyde Griffiths well but, on opening night at least, lacked the vocal punch for effective sonic climaxes. The others -- Jennifer Larmore (the aunt), Kim Begley (the uncle), William Burden (the cousin), Jennifer Aylmer (the other cousin), Richard Bernstein (the prosecutor), and Anna Christy (the chambermaid) -- sing and act well in smaller roles, as does boy soprano Graham Phillips as the young Clyde. James Conlon conducted admirably, but without the forward-rushing abandon that some of the quicker passages seemed to require. Perhaps the orchestra's further familiarity with the score will allow that?

[* Or, indeed, Massachusetts, as the opera may remind.]

Now to a local Met audience -- particularly on a gala night, as Friday's -- what happens elsewhere doesn't matter anyway. Gene Scheer and Tobias Picker's An American Tragedy is, whatever else, the intricate refraction of local concerns that The Great Gatsby entirely failed to become under John Harbison's unfocused eye. (None but Wagner should be his own librettist, and even he could have used a good editor.) For success in that alone the Met may count the venture good. Many in attendance, too.Of course, there's more to it than that. Clyde Griffiths isn't felled by class conflict, after all, nor even by the consumer hunger (the opera gives Clyde this aria soon after arriving in Lycurgus) that pushes him into it. It's a more universal aspect of his charmingly unbanked desire* that brings him to ruin: love, or lust. In this it follows the novel's famous movie adaptation, A Place in the Sun, perhaps more closely than one might have expected. As in that version, Clyde's desire for worldly advancement is embodied -- maybe even subsumed -- by his desire for the alluring, possibility-intoxicated Sondra Finchley, who as perfectly written for Susan Graham (think of her Hahn album, not Octavian) becomes a fairly understandable motive for unfaithfulness. But this, too -- like Clyde's seduction and abandonment of the less colorful Roberta Alden -- is a familiar local story as much as a universal one.

[* Perhaps learned from his parents, who did love God immoderately.]

The first act -- there are two, each about an hour and a quarter -- rushes forward breathlessly; the second builds, with much contemplative breath at the beginning, to a gripping dramatic climax (and a lone plunk). The seamless scene-to-scene

changes of each are enabled by Adrianne Lobel's excellent three-tiered set design, with two levels for action (some simultaneous in two times or places) and the top for complementary scenery. Painted panels slide across the three levels, and combine with occasional solid slide-on set elements to form a great range of stage images. It's a production that takes good advantage of the Met's size and stage apparatus, and might be tricky to put on elsewhere.

changes of each are enabled by Adrianne Lobel's excellent three-tiered set design, with two levels for action (some simultaneous in two times or places) and the top for complementary scenery. Painted panels slide across the three levels, and combine with occasional solid slide-on set elements to form a great range of stage images. It's a production that takes good advantage of the Met's size and stage apparatus, and might be tricky to put on elsewhere.In a sense the drama recapitulates -- as do its somewhat greater forerunners -- the story of its creators' civilization. Act I, moving ceaselessly forward from scene to ever-shifting scene, is entirely Clyde's -- which is to say desire's. Its unbanked force within him, manifesting in characteristically American form (as above), conquers what's before it, triggering and feeding from desires of those around him. So Clyde gets his job, then his woman, then his social entree, while Roberta finds love and Sondra -- who has discovered desire herself in New York (not least, of course, through its consumer opportunities!) -- a playmate and co-dreamer.

These, naturally, can't all coexist -- a far more fundamental problem for Clyde (and society) than the mean-but-incidental snobbery of his cousin or aunt. Act I closes with his idyll of ever-newly-satisfied desires being fatally cracked, as Roberta tells him she is pregnant.

But Clyde doesn't follow the rules that would have him resolve these conflicting desires at the point where their conflict has been unmistakably spotlit. This begins Act II's crime-and-punishment structure. He lets things fester, delusionally (or sociopathically) believing that he can still have everything, notwithstanding others' claims. Against this belief every society must defend itself (as also here), not least because it moves some to kill. For Clyde it's a letting-die, though the legal machinery by which peace in America is kept -- even against the strong sexual and economic passions of the country, this incubator of Act I's desire -- finds him a murderer. Whatever the niceties, Clyde's personal case resolves when he acknowledges to his mother that his inner guilt matches the outer. The transgression that began the act thus ends.

Of Picker's music one might make many complaints fair and unfair, but we should first start with this: it well suits the text and performers of the piece. Picker, at the least, well and correctly judged the dramatic arc of the story and the vocal/character possibilities of the people who were to embody it. Beyond that, my initial general impression was that none of it is boring, but too much of it falls into the slow-rapt and fast-ominous dichotomy that's been too common for too long. (What I miss most in new operas is the cabaletta.)

One might joke about the music being set in 1906, as well as the story -- Picker seems to look more to Janáček than to any critically-approved living composer -- but my main thought at the end was: good, now commission from them another one.

More on this, perhaps, after more hearings.

Finally, no one familiar with singing today should be surprised that the two star-quality instruments in the production are both mezzos, and that they walk away with the performance side of the show. Susan Graham and Dolora Zajick's considerable vocal and temperamental talents are shown off very, very well by their parts. Patricia Racette provides blood aplenty to the veins of Roberta, but -- as hinted above -- not a lot of extra color to her character. (It would take a Lucrezia Bori to add that.) In the lead, Nathan Gunn embodies Clyde Griffiths well but, on opening night at least, lacked the vocal punch for effective sonic climaxes. The others -- Jennifer Larmore (the aunt), Kim Begley (the uncle), William Burden (the cousin), Jennifer Aylmer (the other cousin), Richard Bernstein (the prosecutor), and Anna Christy (the chambermaid) -- sing and act well in smaller roles, as does boy soprano Graham Phillips as the young Clyde. James Conlon conducted admirably, but without the forward-rushing abandon that some of the quicker passages seemed to require. Perhaps the orchestra's further familiarity with the score will allow that?

Saturday, December 03, 2005

The crutch

If, as many fear, NYCO-style acoustical "enhancement" will undermine the art of singing, have not supertitles already imperiled diction and balance? Maybe. I watched pretty much all of American Tragedy without the titles and... was able to make out quite a bit of it. Led by Graham and Gunn, the cast did pretty well in putting across at least the gist of each exchange or solo. But for one crucial lapse: Picker set, Racette sung, and Conlon accompanied the Act II opening -- Roberta's first, textually essential letter scene -- in such a way that I literally couldn't understand a word.

An unfortunate lapse, or something that just wouldn't have happened in a pre-title era? Or both. The house was selling libretti; perhaps it will come off better next time when I've read it.

An unfortunate lapse, or something that just wouldn't have happened in a pre-title era? Or both. The house was selling libretti; perhaps it will come off better next time when I've read it.

Three sentences on An American Tragedy

You know, I'd been thinking "Huh -- a new piece without Dawn Upshaw in it..." only to discover they'd cloned her under the name "Jennifer Aylmer" (debuting).

Ahem, seriously: a great theatrical success, no matter what else one might say about the parts. That "else" (mostly positive) later, when I find a bit of time.

UPDATE (12/5): Rather more than three sentences in my long review here.

Ahem, seriously: a great theatrical success, no matter what else one might say about the parts. That "else" (mostly positive) later, when I find a bit of time.

UPDATE (12/5): Rather more than three sentences in my long review here.

Friday, December 02, 2005

Today

I didn't expect to catch it, but the Today Show did in fact do a nice 6-minute piece just now (from about 8:19 to 8:25 ET, for those who recorded) on the premiere of An American Tragedy, with bits of the score and staging (from, I think, the dress rehearsal) in background.

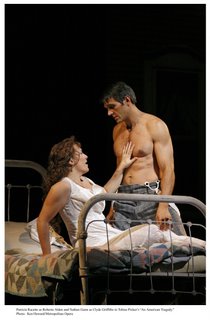

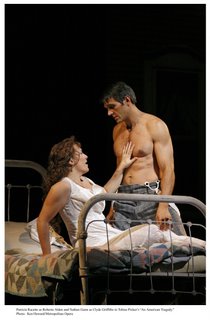

For the curious, it does appear that the obligatory Nathan Gunn Shirtless Scene has been included in the opera.

UPDATE (2:30 PM): A reader sends me this picture, which isn't among the new batch now up on the official site.

UPDATE (2:30 PM): A reader sends me this picture, which isn't among the new batch now up on the official site.

UPDATE 2 (12/5): Welcome, all Balcony Box, Standing Room, and Big Apple Blog Festival readers. More pre-event coverage is in the posts here, here, and here, with thoughts after the actual premiere here, here, and here.

For the curious, it does appear that the obligatory Nathan Gunn Shirtless Scene has been included in the opera.

UPDATE (2:30 PM): A reader sends me this picture, which isn't among the new batch now up on the official site.

UPDATE (2:30 PM): A reader sends me this picture, which isn't among the new batch now up on the official site.UPDATE 2 (12/5): Welcome, all Balcony Box, Standing Room, and Big Apple Blog Festival readers. More pre-event coverage is in the posts here, here, and here, with thoughts after the actual premiere here, here, and here.

Quotes

From some of the principals of tonight's world premiere at the Met...

Gene Scheer, librettist:

Tobias Picker, composer:

Nathan Gunn, "Clyde Griffiths" (protagonist):

Susan Graham, "Sondra Finchley" (the other, richer woman):

Gene Scheer, librettist:

"One would think that a librettist's job is to write the words that will be sung. And at one level, of course, that is certainly what one does. But the truth is that the most important task a librettist has is to create moments that demand to be sung. The words clearly matter, but crafting what is happening in each moment is what makes an opera 'sing,' both literally and figuratively."

Tobias Picker, composer:

Picker has filled his work with lyrical arias and ensemble set pieces, and there is little or no recitative. An American Tragedy, as the composer describes it, is carried forward in an "arioso style." [...] "I think that there's an American flavor to the musical language in this piece," says Picker, who has included an actual hymn from the 1880s ("'Tis so sweet to trust in Jesus") as well as one of his own composition in the big church scene in Act 2. "I hope there is a directness to the music and a simplicity-when it needs to be simple the music is not afraid to be so. When the situation or the emotional moment requires complexity, the music is more dense. My music has a straight forwardness about it. It is clear and direct, like Americans are."

Nathan Gunn, "Clyde Griffiths" (protagonist):

"The more I know the character through the music and the libretto, the more embarrassing I find Clyde. This is not because he's ignorant of certain social subtleties. He has an earthiness that is very primitive, very powerful."

Susan Graham, "Sondra Finchley" (the other, richer woman):

"She's young. She should convey a sort of knowing naïveté. She's early-twentieth-century. She's a strong girl, full of complex social influences, and quite ahead of her time. She has a sexual foray, cares about Clyde yet doesn't show her face at the trial. Still, she sends him that final letter." Graham sees parallels between An American Tragedy and another genuine news story, the recent case involving Scott Peterson and the drowning of his pregnant wife. "But," she qualifies, "I'm not playing Amber Frey."

Thursday, December 01, 2005

Excerpts

The official site of Tobias Picker's "An American Tragedy" now has three audio excerpts from the score, as sung to piano accompaniment "at a special press preview" two weeks ago. The world premiere is tomorrow.

You will need Flash enabled to play these excerpts.

You will need Flash enabled to play these excerpts.

Balancing act

Bertrand de Billy, it seems, takes Gounod's Roméo et Juliette very seriously. (Seriously enough, it's rumored, to oust talented young diva/ham Jossie Pérez from most of the new production run.) It shows a trait that's served him -- and the house -- well in his role as ringleader of, among less over-the-top warhorses, the Met's Turandot circus.* He brings an unusually musical hand to these standards, with a strong sense of rhythm and pace. The sound he gets, though much better than the mere routiniers who preceded him, isn't the most refined... But then again, he's so far done revivals without, I assume, a huge amount of preparation time. The results have been commendable.

Singing actress Natalie Dessay is on the same page, and perhaps pushed this approach. Not that her voice has given out -- it sounds a bit less purely focused, but may now be louder and somewhat darker. The hardness that was evident in her last, between-two-surgeries Zerbinetta run has gone. But stage presence and character have always been similarly-praised strengths.

Between these two principals (and the stage direction part of the production team, which Peter Davis attributes to Guy Joosten), the first half of the evening almost lights up the dull physical production. Dessay-as-Juliet is all youthful motion, whose newly-free newly-adolescent flirtation with Romeo -- culminating in a mock-swordfight -- is a physical revel. O'Flynn was much the same in her own performance, but Dessay goes further and actually inspires Ramón Vargas to his own youthful bounding. Meanwhile she (far more than Vargas) responds marvelously to de Billy's nervous and propulsive waves from the pit: they resonate through her body like ripples in a pond, as the base and contrast of the loving freedom she seeks.

Meanwhile Vargas -- unlike some other notable bel canto tenors of the day -- is, though light-footed, a naturally still man, displaying perhaps the same centered inertia onstage as in the temperament that makes his sweet voice so remarkably pleasant. For all his moving about the stage, it is still Juliet who pursues this Romeo, she who reflects on stage the lovers' precarious position with balance, tension, and some hard-earned grace. But that's enough.

* * *

Yet whether it's the troublesome floating bed business (and its high-concept largeness alone overwhelms many a nuance) or simply an exhaustion of ideas, inspiration quickly peters out after the intermission. Young and nervous becomes young and paralysed without much sign of maturation; no new note is struck in the love-scene to add to the characters' depth. So Dessay is hardly a presence in the tomb, the emotional charge of which therefore (mostly) turns on Vargas' vocal contribution. Surely neither she, de Billy, nor Joosten et al. had that in mind.

[*Incidentally, at least two friends have told me that seeing this Turandot almost put them off opera for life.]

So, in this first new production he's headlined, de Billy -- if the first and third performances were representative -- has pursued the serious path. He keeps a firm rein on the orchestra and singers, pushing them with energetic tempi and phrasing; by no means does he allow the evening to become the sort of relaxed star-singing exhibition that was the early-season Manon. That was a success; just the sort of success for which many come to the Met. But this run hunts other trophies.Singing actress Natalie Dessay is on the same page, and perhaps pushed this approach. Not that her voice has given out -- it sounds a bit less purely focused, but may now be louder and somewhat darker. The hardness that was evident in her last, between-two-surgeries Zerbinetta run has gone. But stage presence and character have always been similarly-praised strengths.

Between these two principals (and the stage direction part of the production team, which Peter Davis attributes to Guy Joosten), the first half of the evening almost lights up the dull physical production. Dessay-as-Juliet is all youthful motion, whose newly-free newly-adolescent flirtation with Romeo -- culminating in a mock-swordfight -- is a physical revel. O'Flynn was much the same in her own performance, but Dessay goes further and actually inspires Ramón Vargas to his own youthful bounding. Meanwhile she (far more than Vargas) responds marvelously to de Billy's nervous and propulsive waves from the pit: they resonate through her body like ripples in a pond, as the base and contrast of the loving freedom she seeks.

Meanwhile Vargas -- unlike some other notable bel canto tenors of the day -- is, though light-footed, a naturally still man, displaying perhaps the same centered inertia onstage as in the temperament that makes his sweet voice so remarkably pleasant. For all his moving about the stage, it is still Juliet who pursues this Romeo, she who reflects on stage the lovers' precarious position with balance, tension, and some hard-earned grace. But that's enough.

Yet whether it's the troublesome floating bed business (and its high-concept largeness alone overwhelms many a nuance) or simply an exhaustion of ideas, inspiration quickly peters out after the intermission. Young and nervous becomes young and paralysed without much sign of maturation; no new note is struck in the love-scene to add to the characters' depth. So Dessay is hardly a presence in the tomb, the emotional charge of which therefore (mostly) turns on Vargas' vocal contribution. Surely neither she, de Billy, nor Joosten et al. had that in mind.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)